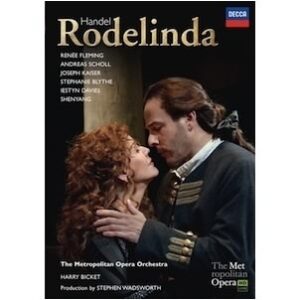

The Met is not known for its Handel productions; the composer would hardly know what to do with 4,000 spectators unless they were on the banks of the Thames. But the house’s 2004 Rodelinda, revived in 2006 and then again in 2011, whence this DVD comes, makes a very good case for Handel-in-a-big-house.

Director Stephen Wadsworth has updated the action from medieval Lombardy to (approximately) the first half of the 18th century—i.e., during Handel’s period in London. The sets, by Thomas Lynch, are gigantic enough to fill the Met stage; it was wise not to miniaturize this opera by, say, building a proscenium within the Met’s proscenium. And they are indeed good looking. By placing them on a moving platform that glides smoothly and slowly from side to side, scene changes are not only easy and quiet, but an entirely new world comes into view.

A handsome, wood-paneled library with floor-to-ceiling books and a desk and chair gives way to a courtyard with statuary and trees; a dark prison in which few details can be made out is equally effective. I might add that all of this keeps the singers near the front of the stage, which helped the intimacy in-house. On DVD it is even better: we can see details while focusing on the singers. Wadsworth keeps singers reacting and moving while da capo arias are performed, and the effect is far less static than it otherwise would be. Martin Pakledinaz has created lavish costumes for these aristocrats. Excellently directed for the small screen by Matthew Diamond, the entire effect keeps our interest through 29 arias, a duet, and a final quintet.

The original production was mounted for Renée Fleming, and she has sung every performance of the opera since. At one point she had the technique for almost anything; everything is a bit more difficult now. The tone remains creamy, her involvement with the text comes and goes with how difficult the music is and where in her voice it lies, and the slight loss of luster (or center) in her highest notes is noticeable but hardly serious. She tires about half way through the opera—she has eight arias, after all—but rallies at the end and it is to her credit that her da capo embellishments are complex. She acts Rodelinda’s predicament well, if without any particularly original touches. Her duet with her husband at the close of the second act—one of Handel’s most beautiful—makes you almost forget that stylistically she sings Handel as if he were Mozart, which isn’t too bad, and occasionally Strauss, whose broad portamentos are out of place in the 18th century.

As the exiled and thought-dead King Bertarido, countertenor Andreas Scholl embodies great Baroque singing, albeit with a voice that occasionally now loses focus. His opening aria, “Dove sei”, is filled with longing, and he sings it with long line, a true sense of where it is going, and great shading. Hours later, Handel gives this character a wild showpiece, “Vivi tiranno”, and Scholl kills with it—fast runs, octave leaps, sharp attacks. It’s a fine performance, worthy of the star castrato Senesino, for whom the role was composed. As his scheming sister, Eduige, Stephanie Blythe can turn on a dime, emotionally: she goes from grief to vengeance with brilliance, all of it believable. She’s a big woman, and she uses her size to appear imperious: it works. Another countertenor, Iestyn Davies, making his debut in the role of Unulfo, almost walks away with the show. The voice is utterly smooth, his agility remarkable, and he dazzles in his second-act showpiece, “Fra tempest funeste”.

The villains, Grimoaldo and Garibaldo, are the lower voices. The former, a tenor, a complex character who is engaged to Eduige so that he can legally usurp Bertarido’s throne (having deposed and attacked him), begins to have bouts of conscience and repents by the opera’s close; indeed, his scene of battling his inner torment in the last act is a great moment. Joseph Kaiser handles his arias—whether vengeful, tender (towards Eduige), or troubled—with style. As his truly evil counselor and friend Garibaldo, bass Shenyang sings with an audible sneer but not always clean coloratura.

Baroque specialist Harry Bicket leads a reduced Met orchestra—with the addition of a pair of harpsichords (one of which he plays to accompany the recits), a pair of recorders, a theorbo, and Baroque guitar—with verve, attention to detail, urgency, and few requests for heavy vibrato.

Picture and sound are superb. As far as the competition is concerned, an updated production from Munich (on Farao) by David Alden is more interesting, and Dorothea Röschmann is a better Rodelinda; but the two countertenors are not nearly as good. Another, from Glyndebourne (Kultur), finds Scholl in better voice but acting stiffly and with Anna Caterina Antonacci a passionate if slightly veristic Rodelinda. You can’t go wrong with any of the three: all give honest, interesting readings of this beautiful, noble work.