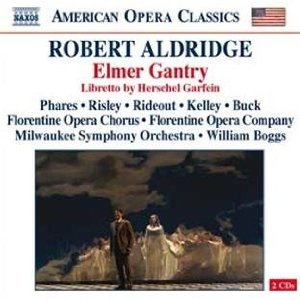

Robert Aldridge’s Elmer Gantry was premiered in Nashville in 2007 and the next year traveled to Montclair State University in New Jersey. It has since been played in Houston, Minnesota, and Milwaukee; this set was recorded live in the latter in March, 2010. Based on Sinclair Lewis’ 1927 novel that centers on a con-man evangelist, the opera took 17 years of effort by Aldridge and librettist Herschel Garfein to bring it to its Nashville premiere; how ironic that it should find a home in the Bible Belt. Granted, some of the barbed, pointed, focused satire of the original has been toned down; those who have read the novel or have seen the 1960 film (which won three Academy Awards and was scored by André Previn!) might miss some of the nastiness (Gantry is a monster in the book; Burt Lancaster plays him as a corrupt charmer, with some warmth), but the points about fraudulent evangelism—possibly more relevant today than any time earlier—are well made.

Those looking for wild tonalities, tape loops, or screaming dissonances from the orchestra that comment on the action will be disappointed with Aldridge’s score, which is tonal and cinematic. You’ll find arias, duets, and ensembles—forms familiar from centuries of opera—all lyrical and well-structured. There’s an echt-American sound to Aldridge’s music, and while I can’t pinpoint exact moments where the likes of Copland and Floyd pop up, the harmonies have that wide-open feel that are immediately recognizable. That is not to say the music is either cheap or glib: it is comfortable and, at the same time, dramatically valid. Aldridge includes marches, hymns, quasi-hootenannies, and gospel music into the score where apt, and he doesn’t linger on them for their own sake—they are in context. The opera runs about two hours and 20 minutes and is broken into many scenes. I was not bored for a moment.

Baritone Keith Phares’ performance of Gantry makes me wish I’d seen the show: his charisma comes through the speakers. It’s a grand, grandstanding performance, whether he’s plotting, seducing, or preaching. Frank Kelley, who plays Eddie Fislinger, a real preacher betrayed by Gantry, may not have the greatest voice, but his hysterical aria at the end of the first act, in which he laughs maniacally while plotting revenge against Gantry, is a show-stopper—and a marvelous coup-de-theatre from Aldridge. Sister Sharon Falconer, a true evangelist and Elmer’s fiancée, is sung by mezzo-soprano Patricia Risley. The character is as pure as snow and clearly obsessed, and Risley makes us believe her; she believes every word she preaches. Lulu, Eddie’s slutty wife, is soprano Heather Buck, and she vocally prances her way into Elmer’s bed with a seductive tune that becomes a duet and then a trio—Eddie acts as voyeur to the situation. Elmer’s old roommate with a strong moral center, Frank Shallard, is well-sung by Vale Rideout.

William Boggs leads this ensemble-filled, busy work with love and discernible glee; the work has great energy and so does the performance. The Florentine Opera Company and Milwaukee Symphony are excellent. I was not expecting to enjoy this as much as I did, but I can recommend it very highly. Maybe not to Pierre Boulez, but to people who enjoy a good, well-crafted show.