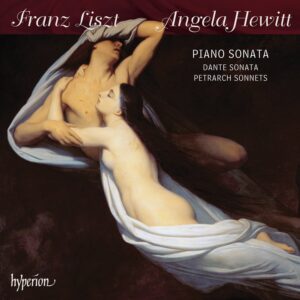

In the excellent and informative booklet notes for her first all-Liszt solo CD, Angela Hewitt writes about how youthful performances of the composer’s B minor sonata helped her win competitions, and expresses her long held desire to record the work. Hewitt’s interpretation will likely attract intense critical scrutiny, given her world-class reputation, plus the fact that excellent Liszt sonata recordings by Leslie Howard, Nikolai Demidenko, Stephen Hough, and Marc-André Hamelin already grace Hyperion’s catalog.

The pianist takes time unfolding the seven opening sotto voce bars, and makes the Allegro energico’s articulation markings distinct, even to the point where she distinguishes a fermata from a double fermata. However, Hewitt holds back the first fortissimo, underplays the exposition’s precipitous agitation in comparison to the first and better of Claudio Arrau’s two Philips recordings, and stretches the eighth-note triplet upbeats in the octave section to the point where they sound like eighth-note duplets.

While Hewitt resists mooning over the Grandioso theme, she pushes it a little too fast for its implicit rhetoric to register. She shapes the lyrical D major theme sensitively, but arguably dawdles over the dolce trills and doesn’t give the fortissimo rising left-hand octave triplets their driving due. However, Hewitt really lets go in the Quasi adagio’s “con passione” measures, while imbuing the slow and soft scales with impressive delicacy and dynamic shading. If her Fughetta is not quite so brisk and imaginatively characterized as Hamelin’s, the 32nd-note triplet upbeats emerge with uncommon clarity. Likewise, Hewitt is one of the few to obey Liszt’s request not to make a ritard in the measure before the Prestissimo octaves kick in, yet she broaches the latter gingerly. Judging from a webcast from her 2014 Asian tour, Hewitt’s Liszt sonata appears to live more dangerously in front of an audience, with more bravura and sweep.

Hewitt’s scrupulous poise also draws attention to lovely details throughout the three Petrarch Sonettos, such as No. 47’s una corda pedal colorings and No. 123’s carefully built-up long crescendos. Yet somehow the music never quite projects over the proverbial footlights. One telling example occurs in No. 104’s introductory measures, where the transitional ritard into the main theme stays on the same dynamic level and falls flat. Arrau, by contrast, generates more intensity by observing Liszt’s marked crescendo.

Too many pianists transform the Dante Sonata into an interminable octave and tremolo study. Hewitt, of course, will have none of that. She brilliantly calibrates and orchestrates the often blocky textures with multi-leveled specificity of color, nuance, balance, and dynamic scaling. Her Apollonian vantage point pulls you in and holds your attention, although one might miss Arrau’s burnished chord playing or Mykola Suk’s compelling sense of narrative. For all of the pianist’s obvious intelligence, expertise, and commitment, I suspect that Liszt is more of an acquired passion rather than an inborn affinity. Should Hewitt plan a follow-up, I’d suggest that the rigor and refinement characterizing her best Liszt playing might lend itself to the composer’s strange late works, or to the harmonic and contrapuntal complexities of the Variations on “Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen”. It’s a thought, anyway.