Well, the plot of Handel’s 1736 Arminio is no worse than many others, and at least we have no returning general/fiancé/son dressed as a woman to make things both complicated and right. In brief: Arminio, a German general, has conquered a bunch of Romans. Varo, his Roman adversary, is in love with Tusnelda, Arminio’s wife. Arminio is currently a prisoner of Varo; his wretched father-in-law, Segeste, a quisling for Rome, hopes to see Arminio executed so Tusnelda can marry Varo.

One must also pay heed to couple No. 2: Ramise, Arminio’s sister, is in love with Sigismondo, Segeste’s son–clearly a conflict of interest. Sigismondo, somewhat of a wuss at first, turns out to be a hero: He frees Arminio, who kills Varo. Segeste apologizes profusely, and Ramise marries Sigismondo. Arminio is not a very strong leader, so that aspect never quite grips us; the fact that Handel was concentrating more on the “love” aspect than the “duty” aspect is made clear by the opening and closing duets for the married couple, Arminio and Tusnelda. It’s unique in Handel’s operas.

It may not be a masterpiece but it doesn’t quite deserve the exile it was given from the day it was first performed (six performances, and that was it). There’s plenty to hear and appreciate in Arminio: this is its second (and better) recording; the first, under the late Alan Curtis, is worthy, but the gender casting here is more accurate (castration notwithstanding), and the characterizations, where there are solid ones, are vivid. And the singing is spectacular.

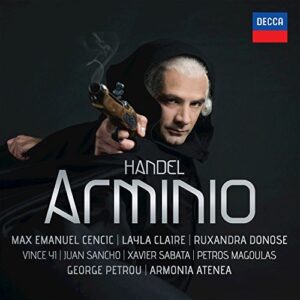

But you’d better like countertenors. The three on this recording give the lie to the theory that all countertenors sound alike: Max Emanuel Cencic, who sings the title role, has a grand, focused, splendid sound; Vince Yi, as Sigismondo, is girlish (even more-so but less lovely than Philippe Jaroussky), and Xavier Sabata is a dark-voiced Tullio, a Roman Tribune, an enemy of the good guys.

For a taste of Cencic’s many sides, try “Dura lacci”, a lament he sings when enchained, the voice dark–and then, moments later, almost as a cabaletta, the fiercely defiant “Si cadro”, filled with acrobatics, long runs, and octave leaps. His voice contains wonderful colors and his singing is fearless, as becomes his character. His last-act “Vado morir” is almost a plaint worthy of Cleopatra or Alcina.

For an entirely different sound and style, Vince Yi’s take on “Posso morire”, which wildly closes Act 1 with runs galore and a very high tessitura, is dazzling. His Act 3 aria, with oboe obbligato (and duet partner), is a stunner too, complete with high-C. Unlike Cencic’s multi-grain sound, Yi’s pure white-bread may tire the listener: he has five arias. Sabata is an entirely different animal: he possesses a dark-hued contralto and impeccable coloratura that bring life to the under-composed role of Tullio.

Bass Petros Magoulas sings a rigidly threatening aria in the first act that defines his cruel character; the voice is rich, perhaps enough to help you overlook the “ha-ha-ha-ing” that enters his melismatic singing. Varo, the Roman general, is sung by tenor Juan Sancho, who possesses a decidedly manly tone, rich in mid-voice (where most of the role lies). Backed up by a pair of gloriously played horns in his third-act aria, he proves a worthy partner, handling the fiorature with unstoppable attitude.

As for the women, Layla Claire, as the lovely, faithful Tusnelda, is a treasure. I can recommend the gorgeous aria that closes the second act, “Rendimi il dolce sposo”, as a test aria: long lined, beautiful, even tone, ideal for a plea to her captor. And what a trill! Listen also to her hopeful duet with Ramise, the voices singing as one, with Claire’s brilliance shining above mezzo Ruxandra Donose. Donose impresses mightily in Act 1 expressing her terror, and really comes into her own near the opera’s close, with a dusky but agile reading of “Voglio seguir lo sposo”, in which she pledges fidelity to her fiancé.

Conductor George Petrou, clearly believing in the power of the opera itself as well as in his superb singers, turns each moment into a truly dramatic event, his Armonia Atenea playing period instruments with clarity and expression. As I said at the top of the review, the opera is not a masterpiece on the level of, say, Ariodante or Alcina, but the performances here are nothing if not masterly.