Early music lovers certainly are lucky these days. The variety and high standards of performance and the equally fine production values of many of the labels that serve this music guarantee listeners an embarrassment of riches–and force difficult decisions for those of us with limited budgets. But these are pleasingly difficult decisions: not only are early music performers just scratching the surface of repertoire and just beginning to discover certain composers and the treasures of certain manuscripts, but almost by definition we know that this “ancient” music isn’t going away anytime soon. There’s enough to keep us interested and satisfied for another couple of millennia at least. And here’s yet another example of how accomplished today’s singers and instrumentalists are–and especially how glorious was the music of 16th-century Spain.

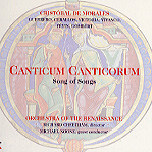

Director/sackbutist Richard Cheetham’s Orchestra of the Renaissance was conceived as a means to explore the performance of 16th century music in which voices are accompanied by wind band. So our ideas about the primacy of a cappella Renaissance vocal polyphony are somewhat tweaked–and delightfully so–in these sumptuous and efficacious vocal/instrumental settings of works by Morales (his mass Vulnerasti cor meum), Gombert (Quam pulchra es), and Guerrero (Ego flos campi), among others. To give further focus to the program, the works all center on the theme of the Bible’s Song of Songs, an inspiring subject, judging from the 13 featured pieces, each of which is a showcase of the composer’s skill in providing the most sophisticated musical framework in service of the elevated sensuality of the texts and imagery. And it obviously was as inspiring for the singers and players as well: these are among the finest early music performances on disc. Richly colored, resonant, note-perfect, and well-tuned, they spring from the ardent expressiveness written into every musical line. And this not only applies to the voices: the (cornett?) solo in Rodrigo De Ceballos’ Hortus conclusus is a lovely, dreamy piece of poetry.

Unfortunately, no information is given regarding the historical/musicological basis for the instrumentation, which I assume was editorial in origin–even though the liner notes provide an eloquent discussion of the music’s background and historical context. Yet the pleasure is in the listening, and it all sounds so right and so beautiful, you’ll be happy to banish such technical questions to a later time.