On the grounds of Prague’s ancient Vyšehrad Castle, high above the right bank of the Vltava river, is a cemetery. Not an “ordinary” one, but the resting place of many of “the most beloved and respected” sons and daughters of the Czech nation—including artists, musicians, writers, poets, politicians, and scientists. A select few of these—the nation’s most revered citizens—are chosen to lie in the “Slavin” mausoleum, above which is engraved a message: “Although they died, they are still speaking.” And that is what we hope will be the enduring truth for all those whose lives, and voices, were cut short by Nazi murderers.

There is always so much we can say when considering the lives and work of composers who were killed, often at relatively young ages, in the circumstances of war—and especially the particularly horrendous circumstances faced by Jewish composers in Europe during the Second World War. The brutality, the senselessness behind the taking of these innocent lives (along with the millions of others with them) makes us feel the loss more poignantly. This was not illness or natural disaster or accident. This did not have to happen.

We are unnerved, dispirited by the question: How different would the world of music have been had these musicians been allowed to live their lives? But we can’t go back; we must look to what we have, what fragments of their imaginations, their skill, their artistry exist and allow us today to appreciate and be moved, not because they died, were murdered, but because their music is worthy of appreciation, eminently artful, and consummately moving.

Of course there’s always the danger of reading too much into the music, assigning some meaning to it that it may not have. Only three of the works presented here were actually written while the composers were imprisoned (the pieces by Hans Krása and Gideon Klein, in the ghetto-fortress-concentration camp of Terezín north of Prague). And yet, those works are perhaps the most technically and expressively sophisticated contributions on the program—and that’s saying something, because virtually all of this music is exemplary, while varied, in its treatment of sound and timbre and in the way each composer exploits both the dramatic possibilities and emotional range embodied in such a small but (in the right hands) potent group of instruments.

A wonderful thing here is that, accompanied by the thoughtful and well-written notes, you feel like you get at least a fair introduction to each composer (if you didn’t already know them—both Krása and Klein have received substantial attention since the 1980s, thanks to the efforts of Joza Karas, whose persistence and pioneering research first brought many of their compositions to light, along with the work of other musicians interred in the Terezín ghetto). And your impression will undoubtedly be positive, your listening rewarded with musical dialogue and vocal interplay and thematic development as fine as in the most engaging theatrical piece. Intense, taut, often playful, (briefly) lighthearted—although, other than with the two Czechs (Krása and Klein) there are no direct connections among the composers on this program, there are obvious similarities in tone, mood, and style, among them frequent references to and inspirations from folksong. There are definite stylistic traces of Schoenberg, Bartók, Webern, Janácek, Ravel, and others, including both Hungarian and Czech composers, whose influence was strong and relevant in post-World War 1 Europe.

Silenced Voices doesn’t refer in the same sense to all of the composers represented here: unlike the others on the program, Hungarian Géza Frid (a student of both Bartók and Kodály) managed to survive the Second World War, living in the Netherlands, having left Budapest in the 1920s. Reportedly he was active in the artists’ resistance while prohibited from giving musical performances. Post-war he returned to giving recitals and seeing performances of his compositions. His Trio à cordes Op. 1–here in its world-premiere performance–makes a powerful impression, its substantial construct and consequential effect belying its early creation by the 22-year-old Frid.

Speaking of youth: the similarly titled work by 19-year-old Dick Kattenburg (who nearly survived the war but was caught in the Netherlands and sent to his death in 1944) shows enormous vitality, intriguing invention, and potent promise, a totally enjoyable yet serious five minutes that easily could have developed into something far more substantial. Hungarian Sándor Kuti’s Serenade for String Trio is a fully formed, mature example of mastery of instruments and form, as of course are the miniature masterpieces by Krása and the slightly more substantial one by Klein, which immediately make their high-caliber presence felt.

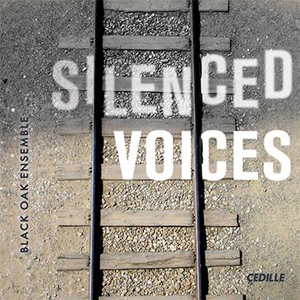

None of these works in any sense identifies with the carefree café scene, nor strikes the fave licks of the waltzing salon partiers of the 1920s and ’30s. This is serious music that bristles and singes and sings, whose creators know strings and how to make three voices into the proverbial sum greater than its parts. And before I forget, the three members of Black Oak Ensemble—Desirée Ruhstrat (violin); David Cunliffe (cello); Aurélien Fort Pederzoli (viola)—are ideal advocates for this music, a threesome that often sounds like six, or like one, and makes the most of melody and makes magic of irregular rhythm and phrasing, of beautiful lines and jazzy utterances, reveling in the gritty groan of bows digging into strings, and finding the joy in rich harmony and an occasional raucous dance. Thanks to such insightful, committed, and masterful performances, those composers, though dead, are still speaking.