Amid the Japanese embrace of Western classical music, certain composers seem to resonate particularly well with Japanese conductors and audiences: notably Beethoven, Bruckner, and Sibelius. This might be gleaned from the fact that Takashi Asahina alone recorded six Bruckner and seven Beethoven cycles while the Japanese-Finnish conductor Akeo Watanabe has two Sibelius cycles to his name.

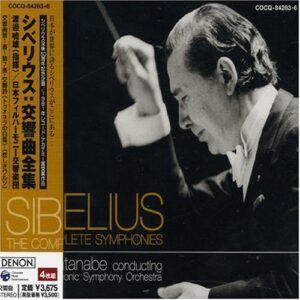

Watanabe’s first set is from 1962 (Nippon Columbia) and made it to the US on Epic LPs and reel tapes where it gained the appreciation of a few connoisseurs, not least for being the first Sibelius cycle in stereo. Alas, it has—to my knowledge—never been re-issued on CD, not even in Japan. (Private transfers are available from the historic audio restoration site KlassicHaus, although that may mean entering a legal gray zone.) The Denon set at hand (extensive texts, but all in Japanese), Watanabe’s second, is from 1981 and also with the Japan Philharmonic Orchestra of which Watanabe was the founding conductor.

If you listen to it from the top, a sense of disappointment will sneak in. The First symphony isn’t anything to write home to Ainola about. The Second is outright bad, both interpretively and playing-wise, with especially the brass’ phrasing, ensemble-playing, and intonation never being secure enough to not leave the listener constantly worried about what might be coming next. The Sibelian glide-and-soar never gets established for a moment, except perhaps in the last dozen bars. The modest sound doesn’t make matters better, and an uneventful Third symphony does little to promise better times ahead. On account of these first three-sevenths of this cycle, it would rank among the least attractive sets out there, just ahead of the curiously weird Rozhdestvensky and Colin Davis’ lackluster middle cycle.

But enter the enigmatic Fourth symphony and the sun comes up. The sparse and gnarly texture of the symphony is traced in caring detail. The primal energy and spooky veneer of the second movement come out nicely, as does the solemn flow of the third. And everything that was missing in the Second symphony comes through in the Fifth, culminating in a powerful finale of the first movement and in the final movement with now perfectly secure playing and very neatly paced closing chords, judiciously balanced between lingering anticipation and abruptness.

In the Sixth, more recent recordings have shown how much more detail of the dense-but-light inner workings can be heard (Storgårds, Kamu II), but the playing and pacing is convincing in its middle-of-the-road way, so no particular complaints here. In the Seventh, finally, the brass is like new-born, with a very subtle, moving vibrato and ever accurate.

Two fillers—a seamless Swan of Tuonela and unpretentious Valse Triste—show more of Watanabe’s good Sibelian side. The orchestra keeps a fairly neutral balance between sumptuous (think Segerstam II/Ondine) and light transparency (Sakari/Naxos and Berglund III/Warner). It isn’t particularly luminous-sounding (Karajan/DG) or overtly energetic (Karjan/EMI), but it does its job very creditably. Yet with so much great competition and hampered by ordinary, slightly fuzzy sound, this set would be only a good also-ran, a curate’s egg, even if the first three symphonies were better done. Watanabe fans might find much… Who am I kidding? This simply isn’t competitive.