John Eliot Gardiner has been doing Bach for a very long time (not to mention Handel and Brahms); he and his Monteverdi Choir have made some fine recordings of works by the Leipzig master over the last 30 or so years. And you would hope that one of the happy consequences of such a long relationship with a composer would be performances offering a mature, reasoned interpretive view born of study and insight gleaned from countless performances. Unfortunately, what we have here, although technically very solid and vocally unassailable—it is, after all, the Monteverdi Choir—is something more along the lines of an assault rather than an artistic musical endeavor. A barrage of Bach in which Gardiner seems to think that hyper-dramatic expression is the key to these motets, whose writing, with the possible exception of some parts of Komm, Jesu, komm and Jesu, meine Freude, are as straightforward and unadorned as anything Bach conceived for choir.

Clear articulation and artful, stylistically aware phrasing are one thing—but when these things are so mannered and affected and deliberate as here, every note of melismatic passages punched to within an inch of their lives, the relentless reams of machine-gun-like “ha-ha-ha-ha-ha’s” in the opening of Lobet den Herrn leaving you looking for the exits, Bach’s music is relegated to nothing more than an acrobatic feat. The Alleluia coda in the same motet is unreasonably—indefensibly— fast, so again we are subjected to the very un-musical rat-a-tat-tat vocal articulation required to delineate the quickly escaping notes.

Jesu, meine Freude is almost angry with its explosive metrical accents, as if the choir is saying “take that, Jesus”, instead of “Jesus my joy, my heart’s delight…” The inappropriate hammering of the texts in the first four movements undermines the impact of the perfectly appropriate violent outbursts in the fifth movement. The entire opening section of the glorious Singet dem Herrn builds to such a frenzy that we just hope it stops before someone gets hurt.

Where does this aggressive approach to the motets come from? Certainly not from the latest Bach scholarship; rather, this seems to be solely Gardiner’s affliction, er, vision, and you have to hope that it’s not catching. There was no sign of it on Gardiner’s analog-recorded set of motets (plus three cantatas) for Erato in 1980, also with the Monteverdi Choir, which remains one of the best versions on disc (even the liner notes for the new set are recycled and somewhat reworked from that earlier release).

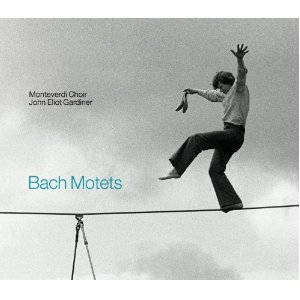

I have praised Gardiner’s work over the past 25 years—his Solomon remains one of the great Handel recordings; many of his Bach cantatas are exemplary; and I love his unique and intelligently conceived Brahms Requiem; but this display of vocal pugilism is a misguided imposition of a conductor’s imagination on works inherently resistant to fussy manipulation. Credit and thanks is given to high-wire artist Philippe Petit, who contributed his image to the CD cover. Is there some symbolic meaning here? Perhaps we could say that at least a high-wire artist absolutely knows his limitations and uncompromisingly respects the integrity of the medium in which he’s working. If you want to hear these works without pretension or stylistic affectation, try Gardiner’s 32-year-old Erato recording (a two-disc set), or the excellent recording from Peter Dijkstra and the Netherlands Chamber Choir from 2007 on Channel Classics.