What is it about Bach’s Cello Suites that makes them so eligible for transcription? Primarily because, on a mere four strings somehow attached to a wooden resonator, Bach has written fully-contained music, needing no other thing and no other instrument to reveal itself fully. That is, Bach presents a continuous flow of music that provides all his ideas of harmony, counterpoint, and melody with only one player, who only occasionally plays more than one note at a time. This is music that does not depend on instrumental color, but rather on the intrinsic logic of the notes. And in Bach’s hands, that logic is compelling, no matter how many hours one spends with those notes, and quite independent of the instrument.

The latest addition to instruments that have taken on the challenge of the Suites is a Cretan Lyra, an ancient bowed instrument that predates our modern violin family by several centuries. Pear-shaped, the Cretan Lyra is held upright on the lap, has three strings, and eight sympathetic strings strung below the fingerboard. Its origins are obscure–perhaps dating to the 10th century. It is central to the traditional music of Crete and other islands of the Dodecanese and the Aegean Archipelago, where it is still immensely popular. Good performers are revered as much as famous footballers.

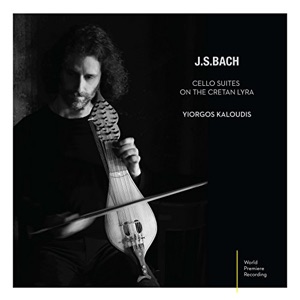

Yiorgos Kaloudis, the Greek cellist, has chosen it for his performance of five of Bach’s suites (he excludes the 6th suite, which presents special problems as it was really written for a five-stringed cello piccolino). The most striking aspect of the instrument, when compared to members of the modern violin family, is not its three strings, but the method of performance: the strings are not stopped (pressed) from above, but instead the nail of the player’s hand is placed up against the side of the string. This gives the lyra a distinctly different sound from a member of the violin family, since the nail offers a hard edge rather than the soft pad of a finger tip. The sound is more resonant, and more brilliant.

That impression is fully realized in Kaloudis’ Prelude to Suite No. 1, in G major. Never mind that his bowings don’t conform to what we think is the most historically accurate edition of the music, the one copied out by Anna Magdalena Bach, J.S.B.’s second wife, who did yeoman’s service making clean copies of his music. Bowing and articulations are thorny issues that I don’t plan to address in this review. The performance is musical and pleasing and has shape, meaning that he phrases and breathes, subtly taking into account the harmonic and melodic implications of the music, rather than simply playing the notes mechanically as some performers have done.

The subtlety does not last long, unfortunately. As early as the next movement, the Allemande, Kaloudis’ desire to linger on harmonically expressive notes begins to be noticed, and eventually reaches new levels of exaggeration that destroy the flow of Bach’s music–which, after all, is based on the dances of the Baroque era: Allemande, Courante. Sarabande, Minuet, Bourée, Gigue. A good performance can never ignore the underlying pulse. Kaloudis ignores it frequently. The D minor Allemande is so unbearably distorted as to be hardly recognizable, presented as a wandering meditation. The Courante of the same suite suffers from an excessive use of pauses after each phrase. Kaloudis quite misses the point of the Sarabande, with its weight on the 2nd of the three-beat measure. By making a very noticeable pause between the 1st and 2nd beat right at the start he destroys the character, removing any sense of necessity as the music proceeds. The Prelude of Suite IV in E-flat major is provided, intolerably, with an extra eighth-note rest at the end of every measure.

On the other hand, the Bourées of the C major suite are charming, apart from a few unfortunate pauses here and there, and the Gigue of the C major suite (III) comes across very well. Nevertheless, this recording of the Suites is not a mixed bag. I cannot recommend it. While the sound of the Cretan Lyra is refreshing and wholly acceptable as a vehicle for these magnificent pieces, the performance leaves far too much to be desired. There is no intrinsic reason related to the Cretan Lyre that requires the suites to be played in such a quirky manner. Kaloudis is a trained cellist, as he proves decisively on occasion. But the decision to turn these Suites into his private arena for experimentation will not please many.