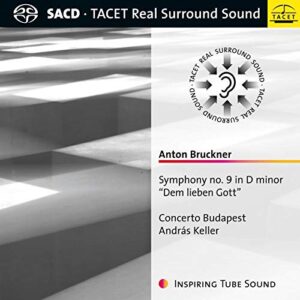

If you dig deep enough into this Bruckner Ninth, if you are set up for SACD-Surround Sound and have no neighbors, and if you care about orchestral nuance more than goosebumps, this recording by Concerto Budapest might be for you. There is no doubt that András Keller (of Keller Quartet fame) has turned this full-fledged symphonic orchestra with its 100-year history around, having transformed a third-rate band into a classy ensemble that, on a good day, can outplay any orchestra in neighboring Vienna. Not all of this comes across on this recording on Tacet. But in a glut of good and great Ninths, it struggles to stand out.

Audiophile “Tube Sound” touts the cover. “Sympathetic distortions” might argue the cynic. Meanwhile, what gives the Tacet recordings their undeniable quality probably are the classic old-school microphones they use, rather than any tubes in the recording chain. Alas, because of the wide dynamic range, much of that never gets to bear, unless you turn it up to the point where the peaks will send your tumbler quaking. The first impression is therefore rather nonchalant. A fine run-through, not outstanding but well done. There’s nothing crass about it, nothing brash. There’s no ostentatious air of incense about the last movement. Nothing sounds particularly mighty or powerful. The tempos are middle of the road. Accounts like Haitink’s with the Concertgebouw from 1981 (a dark horse classic!), Dohnányi’s gripping Cleveland take from 1988, or his regal 2014 interpretation with the Philharmonia from Salzburg all work up a dark storm in the first movement, sturdily and relentlessly marching forward. Keller and Co. seem to sail before an altogether lighter breeze.

Thankfully, their interpretation is not without its upsides. What you get instead of ferocity are lots of exceedingly well-played delicate and soft passages—the kind that would force you to listen very closely in concert, but might let your mind drift when listening to a recording. Listen to the end of the first movement (starting at letter X): soft as butter, sophisticated and nuanced. The strings—especially the first violins (although short of what they are capable of in concert)—are smoothly working through the pianissimos and pianos. It’s perfectly possible that subtlety in Bruckner needn’t actually be a virtue. The fact that beneath a calm surface, this rendering by the Concerto Budapest offers depth, not indifference, is heartening. But it’s not enough to make it rival classics like any of the above-mentioned or Wand’s Apollonian and Jochum’s older and more Dionysian takes.