Ferruccio Busoni’s 1915 edition of Bach’s Goldberg Variations plays freely with the original text, taking an occasional line up or down the octave, while either embellishing notes or outright changing them. Furthermore, Busoni suggests that the repeats should be omitted, as well as variations 3, 9, 12, 16, 17, 18, 21, 24, and 27.

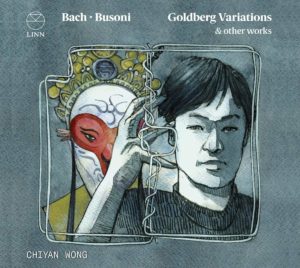

History, of course, has ruled in favor of pure, unadulterated Bach. Yet the Hong Kong-born pianist Chiyan Wong makes a persuasive a case for Busoni’s aesthetic by virtue of his impeccable technique, wide dynamic range, dead-centered sense of rhythm, pellucid touch, and astute polyphonic acumen. It’s a more refined, less forthright approach than the altogether grander conception characterizing Sara Davis Buechner’s sadly out-of-print premiere recording of the Busoni edition on Connoisseur Society. Yet no matter how entangled the texture or busy the counterpoint, Wong’s control and clarity never flinch for a second.

These pianistic qualities similarly inform his Chaconne. Wong may not clarify the elaborate details to Hélène Grimaud’s intense specifications, nor match the impulsive sweep of Alicia de Larrocha’s first Decca version, but his sheer poise and unified pacing deserve the highest praise.

The coolness and transparency Wong brings to Busoni’s Sonatina No. 4 differs from more rhetorical accounts by Paul Jacobs and, more recently, Roland Pöntinen. Whose do I prefer? Let’s say my head goes with Wong, but my heart remains with Pöntinen. One might describe Wong’s inversion of Bach’s minor-key Variation Fifteen as a “Busoni outtake”. He articulates the canonic lines as if each emanated from its own piano: the aural equivalent of three-dimensional chess. I can only imagine Wong’s sophisticated artistry in other repertoire; hopefully Linn has further plans in store with this gifted pianist.