Despite, or more possibly because of Claus Guth’s cold, distancing direction on Michael Levine’s even chillier and cruel sets, this performance of Leoš Janácek’s Jenufa, recorded at Covent Garden in October, 2021, packs the type of disturbing punch we rarely get from a staged production. We begin not outdoors near a mill as indicated, but in a dormitory for babies taking up the whole of the stage’s perimeter, each child suspended in its cradle from the ceiling, watched over by unmoving, severe women in black who sit next to beds. This is motherhood? Forbidding. Joyless. Colorless.

The second act is set in the cottage where Jenufa has been hidden away, overseen by Kostelnicka “to hide her shame” of having a baby born out of wedlock. But it isn’t a home; it’s a cage surrounded by levels of wire. The women are in a prison together. The empty stage for Act 3 is strewn with late-autumn leaves and is otherwise colorless, save when the marriage festivities are about to begin and a few hangers-on wear jolly local-color outfits that come across as garish rather than merry.

Some of it is heavy-handed, to be sure. The town’s women march silently in the background of Act 2 in all black with pointed bonnets that make them seem like a murder of crows. Unsubtle enough, but then appears a “real” giant crow that perches on the roof. The oppression and rigidity is underlined again and again. You can’t escape it, which I guess is the point. Dancing is clumsy and joyless in Act 1, which begins in a lighthearted fashion and then settles into cruelty and grief. This is universal oppression, in a ghastly, quasi-expressionist mode. It weighs everyone down.

I have seen Jenufa on stage a couple of times and on DVDs a couple of times. It is always a visceral experience, but this one acts as a punch to the solar plexus. In addition to the relentless sets and costumes, there is no real light: Even Grandmother Burya, the sole figure of warmth in the opera, is a black-clad, upper-crust harridan with her gray hair in a secure bun, and in the person of mezzo Elena Zilio, she elicits something akin to terror.

The plot, in brief: Jenufa is slashed with a knife by Laca, a jealous boyfriend; she has an illegitimate son by Steva, while being hidden away out of shame by her bitter, rigid, entirely misguided stepmother. Steva refuses responsibility. The stepmother, desperate, drowns the child without telling Jenufa. Nobody asks questions until they accidentally answer themselves: in the last act, with the spring thaw, the frozen, dead baby is found. All hell breaks loose.

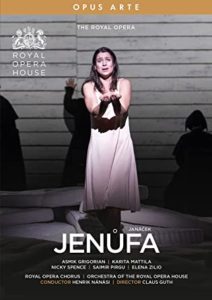

The casting, and in particular Jenufa and Kostelnicka, are unarguably the finest to be heard today. So brilliantly has Janácek fashioned the work that one character could not exist without the other. Asmik Grigorian, dark, slim, her movements small and tight as if she hardly wants to be seen, still manages to be the center of our world: each phrase, each interaction means something. Pleading with Steva, the man she loves, trying to protect herself from the advances of Laca, terrified and horrified by Kostelnicka’s rigidity, Grigorian uses her focused, good-sized lyric soprano the way she comports herself–with an elegance and backbone that is never overwhelmed by Janácek’s orchestration. Her second-act prayer could make a stone bleed.

In the second act we realize that Jenufa’s torment and heartache have been transferred to Kostelnicka, and their relationship has become a study in grief and shame. In the person of Karita Mattila, previously a fine, moving Jenufa herself, Kostelnicka is a living embodiment of both suffering and rage, confusion and certainty. The whole second act is a series of almost overwhelmingly strained confrontations between Kostelnicka and the other three major players–and it culminates in a Mad Scene during which we can almost see Kostelnicka’s hallucinations. Body language, snarls, desperate, repeated high notes–there seems no separation between singer and character.

The two men are equally strongly cast. The slick-looking, unreliable Steva is Saimir Pirgu, attractive and self-involved, recognizably despicable as the most spoiled lad in town–his family owns the omnipresent-invisible Mill. Never in-your-face, Pirgu’s physicality always seems a quiet menace. Of course Laca seems the more menacing, here sung by Toby Spence, a big man sometimes squeezed into formal clothing that looks uncomfortable. The more awkward of the men, his desires simmering and then boiling over, Spence has an almost Heldentenor sound that rings out clearly. Director Guth keeps the other characters minor or inactive, onlookers and willing participants in the village’s cruelty.

Henrik Nánási leads the cast and Covent Garden forces with a scary inevitability–the judgments of the townsfolk are as omnipresent as the grinding of the mill Janácek sets up, and the tortuous, eerie xylophone tones are like the clacking of bones. Forward propulsion never stops, and when, in the opera’s final moments, after Kostelnicka’s final frenzy, Laca and Jenufa agree to wed, the stillness and canny warmth and forgiveness coming from the orchestra makes it all seem like a relief.