For some period during what we now call the Renaissance and Baroque, it was popular practice for vocalists and instrumentalists to embellish or ornament a melodic line by dividing longer note values into many shorter, more elaborate figures as a means of variation. This was nothing so “ordinary” as a little trill or turn, or even a run up or down the scale (although it could include such devices); in fact, we have a modern version of this practice common among most of today’s young pop singers–so if you’ve ever heard one of them sing, say, The Star-Spangled Banner, and think they’re never going to get to the end of a phrase, you know exactly what I’m talking about.

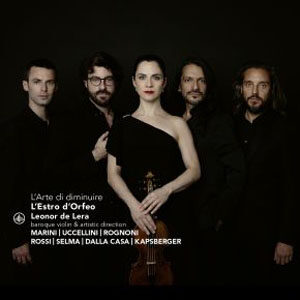

Yet, unlike today’s performers, who in these situations are all about sheer emotive expression (and who have no allegiance to things like tempo), these early singers and instrumentalists spent much time actually studying the techniques, which were codified and taught, providing the ways and means to fill the spaces in between notes, introducing, in the most refined manner, as many thrills and spills, flights and flourishes as possible before the demands of tempo and the need to get on with it forced the melody on its way. You may have surmised that I’m not (and truth be told, never have been) a fan of this practice (then or now), the fad of choice and more than that–an essential test of a solo performer’s credentials for a period. An art? Yes, I agree; but necessary? Or in any way a value-added endeavor? I admit that I said as much to the proprietor of this recording, violinist and artistic director Leonor de Lera, when she inquired about a review. We don’t promise anything, and I will very likely not have a positive impression, but I would listen. I was wrong–about the negative impression.

This is, for all its immersion in “diminution”, the relevant term for this practice of variation and embellishment, is one of the more attractive, engaging, and eminently repeatable recitals you will hear of 16th and 17th century music for strings–baroque violin, gamba, viola bastarda, theorbo, baroque guitar, harpsichord–and rather than a “distraction”, as is my usual complaint, those embellishments almost invariably enhance the melodies and juice the rhythmic energy, melding neatly into the overall flow of the lines of the supporting instruments.

De Lera is an excellent–virtuoso–violinist, and she strives with this program to introduce us to the various compositional forms that tended to incorporate this lively variation style: transcriptions of motets or madrigals from celebrated composers (tracks 3 & 4); arias (track 6); works highlighting the viola bastarda, a viol with exceptional range ideal for playing diminutions (track 7); lively, short, dancing popular tunes (track 13 ). Composers, both familiar and not so well known, include Uccellini, Kapsberger, Marini, and Rossi, as well as De Lera herself, contributing modern but wholly compatible companions to the early works. De Lera’s sonorous, delicately-spun lines and beautifully integrated ornaments are on display everywhere, as are similar offerings from her colleagues, all expert players and ideal ensemble partners.

But, there are one or two reminders of this style’s more tedious tendencies–one of them being De Lera’s version of Giovanni Felice Sances’ Usurpator tiranno, a nearly seven-minute-long grind over a relentless, repetitive ground bass (please, make it stop!). And then there’s the concluding (nearly five-minute) “Tarantella” that sounds totally out of place, like a leftover from another recording. You may disagree, of course, and if so, all to the good. All I can say is that, as a very skeptical listener in the beginning, I was won over.