There are few things more wonderful in the life of a record collector than a really great recording of a repertory warhorse. It’s not just because greatness provides its own justification. There is always the suspicion, especially after hearing dozens of merely adequate performances of a work such as Dvorák’s Eighth, that its charms are wearing thin; that its status as a “classic” remains more a function of institutional laziness, because it’s “easy” music that everyone plays and takes more or less for granted.

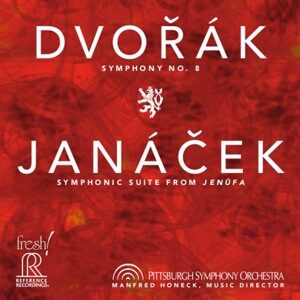

Then, along comes a performance by a conductor who loves the music, who has genuine ideas about how it should go and what it reveals, who leads a great orchestra in a performance that makes us listen to the piece afresh, and who reaffirms our belief not just in this particular work but in what it means to be a “classic”. Manfred Honeck and the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra offer just such an interpretation. Honeck’s personal touches are numerous and completely winning. There are the uproarious horns in the finale, and the delightfully warm phrasing of those “do-nothing” variations just before the boisterous coda, or the freedom with which Honeck handles the “birdsong” motives in the Adagio, the repetitions slightly varied so that the music comes spontaneously alive.

However, the real value in Honeck’s ideas isn’t that he has them–lots of conductors do–but that they invariably suit the music’s expressive point. In the coda of the first movement Honeck steps up the tempo to create a maximally rousing conclusion, and the effect is thrilling. I vividly remember how a Gramophone critic praised Claudio Abbado’s “refusal to whip up excitement in the first movement’s coda,” or words to that effect, at this same moment. That review has haunted me as a symbol of everything that is wrong with modern criticism, never mind modern performance. Here is Dvorák, doing everything that he can to “whip up excitement,” and the performers aren’t supposed to behave similarly? In short, Honeck gets it. He takes the music where it wants to–needs to–go, and in the process gives us one of a handful of shatteringly great recordings of this perennial favorite.

In addition, the coupling is much more than a mere makeweight. Honeck “conceptualized” this suite from Janácek’s opera Jenufa, and it was realized by Tomás Ille. It’s beautiful–more substantial than the rival suite on Naxos, less repetitious, and with one exception better organized. Most of the folk-dance music is here, but there is also some of the wild material from the end of the second act, which is very effective and offers something of the emotional charge of the original. There is more to this music, after all, than mere picturesque cuteness. The exception just noted occurs in the placement of Act 2’s closing pages just before the opera’s final duet, with the result that the suite seems to end twice.

Never mind: this is a substantial and valuable coupling to the symphony. It’s just as spectacularly played and, in vintage Reference Recordings fashion, sensationally engineered. Releases of this quality offer more than just an enjoyable listening experience. They are events of profound beauty and musical significance.