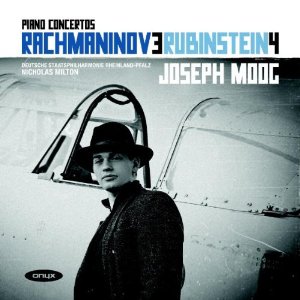

Among the great Russian piano concertos, Anton Rubinstein’s Fourth in D minor strongly dominated the late 19th/early 20th century playlists until Rachmaninov’s Second and Third concertos displaced it. Still, a handful of Romantic virtuosos kept the D minor alive: principally Josef Hofmann and his pupil Shura Cherkassky, not to mention a few fair-to-middling early LP-era attempts.

The young pianist Joseph Moog’s scintillating virtuosity and knack for uncovering inner voices positively delights in all three movements, and yields nothing to Marc-André Hamelin’s extraordinary 2005 Hyperion recording. One notable difference between the pianists, though, concerns the first-movement cadenza, where Moog charts a steady, Apollonian course by underlining expressive points by means of voicing and change of tone color. By contrast, Hamelin applies similar, energetic dynamic surges with a wider degree of rhetoric and melodic inflection. The resonant ambience sometimes creates diffusion in loud orchestral tuttis that emerge clearer on Hyperion, yet the German orchestra certainly plays well, even if the strings do not quite match their BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra’s counterparts for ensemble unanimity.

The same reservations apply when comparing Nicholas Milton’s spirited podium work against the clearer and more transparently engineered Dallas Symphony Orchestra under Andrew Litton in the Rachmaninov Third concerto. For the most part, Moog’s fast tempos and subjective phrasings, accents, and dynamic alterations strike a middle path between Argerich’s volatile temperament and Kocsis’ classicism.

During solo sequences without the orchestra, Moog takes advantage of the spotlight, and lets his imagination run wild as he highlights the thick piano textures’ inner counterpoints (both real and implied) and daringly stretches out the first-movement cadenza—he opts for the “simpler” yet musically more effective cadenza that Horowitz, Argerich, and the composer himself favored, rather than the thicker, heavier and more difficult alternative that unfortunately remains the fashion among young pianists (either thank or blame Van Cliburn for making it stick!). It was a great idea to couple “Rocky Three and Ruby Four” together on disc, and don’t let my small reservations prevent you from investigating these stimulating performances.