Ideology has done much to shape how we listen to baroque music. There was, for one, the one-voice-per-part coterie around Joshua Rifkin that insisted on undernourished performances of cantatas and now-no-longer “choral” works. Analogously, in instrumental works, the concertos have been recast (or restored) as chamber works, also one-voice-per-part. This at least is less controversial, because size-wise that’s exactly what Bach himself did to his earlier, beefier works written in Köthen when he transcribed and down-sampled them for the purpose of performances at Café Zimmerman in Leipzig.

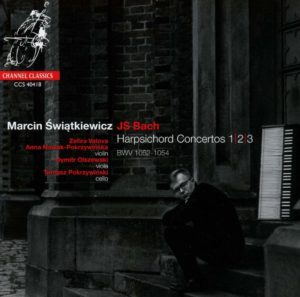

Happily, it turns out that the number of performers matters very little in Bach: Truly musical interpretations can make any approach shine. Case in point: Jos van Veldhoven’s magnificent Passion recordings or Sigiswald Kuijken’s one-year cantata cycle. Often these economical lineups have an edge on agility and bring a certain tenacious bite to the proceedings. That’s not quite what happens with Marcin Świątkiewicz’s recording of the first three Bach harpsichord concertos (BWV 1052-54), which feature him and a string quartet of colleagues.

Everything is rather wonderful about the performances. There’s the individual, tasteful but never over-the-top embellishment. The tempos are on the fast side—the slow movements especially bubble and sparkle at a crisp clip. The full sound of the five players belies the small ensemble. Świątkiewicz’s three different and meticulously chosen harpsichords aren’t much more in the foreground than Andreas Staier’s copy of a Hass instrument pitted against the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra’s 3-3-2-2-1 setup. And actually less so, when Staier also adopts a one-voice-per-part approach for BWV 1053 (except that Staier retains the double bass, which Świątkiewicz eschews throughout). Speaking of Świątkiewicz’s three harpsichords (all modern copies), they are a bright and angelic French Pascal Taskin instrument for BWV 1053, a lyrical-rich Flemish Ruckers for BWV 1054, and a slightly rigid German chimera-type with a booming 16-foot register for the grander BWV 1052.

This is all good and well, but something is missing. The three concertos—even making allowances for Bach at Köthen having had his flashiest, least profound period—flit by as if nothing had happened. Zooming in on the recording, the energy is definitely there, but zooming out, it dissipates. I suspect it is the combination of fast tempos and the sound that has Świątkiewicz’s and his ensemble’s notes run into one another just a bit. Rightly or not, that’s what you might expect from a larger ensemble (although it’s certainly not the case in the best of these, like Concerto Copenhagen with Lars Ulrik Mortensen), but not from a quartet. But why sacrifice a touch of pleasing orchestral heft when you don’t even get total clarity in return? Staier—not that his genteel Harmonia Mundi recording is exactly bursting with energy either—parses the notes more deliberately, with more air between them and subsequently a more pronounced enunciation.

Someone who is also really good at this? Trevor Pinnock, in his classic Archiv recording which still holds up very nicely after exactly 40 years. (Tempus fugit!) You cannot hear Pinnock’s instruments (Blanchet and Ruckers copies) in as great detail as those on this Channel Classics recording, but the music comes out more assertively. And that’s ultimately what matters.