Felix Mendelssohn’s First Piano Concerto in G minor is hardly a youthful effort, seeing that at 22 Mendelssohn was already a grizzled veteran and roughly one third into his entire compositional career. Still, it’s a brilliant, frothy little thing that fits right in there with the concertos of Kalkbrenner, Moscheles, or Chopin. The follow-up, seven years later, in D minor, moves more toward Brahms, if only by a smidgen. It’s considerably more symphonic, with hints of the Scottish Symphony hanging over it, and a moody dark cloud over the central Adagio. Both are eminently worth hearing, yet a little forgettable, which is why every new recording feels like the discovery of a nearly overlooked gem—when there is, in fact, a whole slew of recordings (many of them very good) from Serkin to Bezuidenhout by way of Periah, Schiff, Hough, and many others.

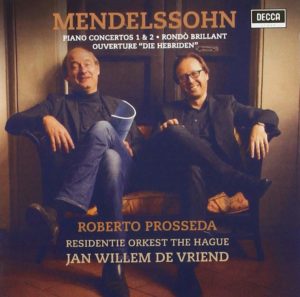

So what to make of Roberto Prosseda’s take on Decca (Italy) with Jan Willem de Vriend and the Hague Residentie Orkest? Right bang in the middle of the upper tier they go, a solid effort in the best sense, garnished with the Rondò Brilliant for orchestra and piano and a fine but unspectacular Hebrides Overture (aka Fingals’ Cave).

Prosseda has been busying himself with Mendelssohn for a decade or so, recording all of the composer’s solo piano music in the process, as well as the reconstructed Third Piano Concerto with Chailly. Granted, Prosseda does not muster Jean-Yves Thibaudet’s glitter-and-be-gay sparkle, which is paired with Herbert Blomstedt’s somber brilliance leading the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra (Decca). Nor does he have the immense delicacy of touch and tight orchestral interplay of Lisiecki and the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra (DG). But not attaining reference-recording status doesn’t mean he and his collaborators don’t hit all the buttons.

Prosseda’s effortless technique (on a Fazioli) splashes sunshine over the music without underplaying the few dramatic moments. Those are in good hands with de Vriend, who has shown himself a sensitive Mendelssohn-conductor with his own symphony cycle (a particularly good Second!). You won’t get the dark intensity from de Vriend that Chailly has shown in some of his Mendelssohn, but you get the necessary heft and grip that keeps the music from slipping into white-gloved boredom (Helmchen/Herreweghe, for example, fall victim to this). Seek this out—or one of the mentioned versions—to cover the repertoire in your collection, if you haven’t already.