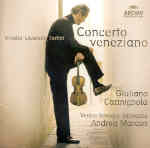

This disc is really something special. Collectors are so spoiled for choice in the baroque repertoire at present, particularly on period instruments, but even in a glutted market this disc stands out for imaginative repertoire selection and outstanding interpretation. It’s particularly gratifying, in these days of complete editions of everything, to see a discerning artist like Giuliano Carmignola choose four remarkably diverse works by three different composers, and simply play the living daylights out of them. The result roundly disproves the notion that Italian baroque violin concertos all sound the same, a point made even more forcefully by imaginative continuo work (on harpsichord, lute, and organ) by the Venice Baroque Orchestra that helps to emphasize each piece’s individual character.

The two Vivaldi concertos, for example, couldn’t be more different. RV 583, subtitled “in due cori”, is a dialogue between the soloist and the two opposing orchestral groups, sometimes elegant, often virtuosic, and Carmignola’s account of the beautiful central chaconne is haunting. The E minor concerto RV 278, on the other hand, is dramatic, passionate, and intense almost to the point of lunacy in its outer movements. The entry of the solo is a moment of high drama that Carmignola clearly relishes, and the entire work often sounds more like one of the more emotive and spasmodic creations of C.P.E. Bach than it does the coolly patterned tune-making of The Red Priest. The orchestra attacks this later work with an unbridled ferocity that never turns crude, and both concertos enjoy the distinction of ranking among Vivaldi’s largest, lasting nearly 15 minutes apiece.

Locatelli’s Op. 3 No. 9 is also a very large work (almost 20 minutes, even at “authentic” tempos which tend to be quick). It’s one of the works contained in the collection “L’arte del violino”, and it features extensive solo “capriccios” in its outer movements. Here another important characteristic of the these performances becomes especially audible: Carmignola’s willingness to take risks. In the finale, for example, he negotiates the Bach-like polyphony of the central capriccio quite freely, in a way that at once celebrates the music’s virtuosity and still suggests its roots in improvisation. His intonation in multiple stops is particularly impressive, as is his variety of articulation, smooth legato, and warm tone. In short, he communicates in a way that highlights the vocal nature of much of the melodic writing, and establishes a very real rapport both with the members of the string orchestra (several of whom have solos as well) and with the listener.

This vocal quality, particularly of the intimate kind, is nowhere more pronounced than in the final concerto, Tartini’s D. 96. The difference between this work and Vivaldi’s pieces can be likened to the contrast between Mozart and Beethoven, respectively. Mozart’s wit and pathos is Beethoven’s jollity and passion. Carmignola clearly understands the difference: much of his playing here, even in the virtuosic outer movements, is more lyrically oriented. As a bonus that sets the seal on this marvelous concert, you also get Tartini’s alternative slow movement in which he admonishes the soloist to create in tones the following text: “In streams, in fountains and in rivers, run, bitter tears, until my harsh anguish is consumed.” Now I ask you, who wouldn’t want to hear that? So do yourself a favor and buy this magnificently played, perfectly recorded disc. It’s an instant classic. [4/30/2005]