Jennifer Higdon’s String Poetic is a major work–substantial (20-plus minutes), significant (conceptually and technically), and successful. In other words, this is a composition of, by, and for the violin and piano, a celebration of instruments as much as it is a tour de force for the players. The piano’s bold opening announcement tells us that no time will be wasted on introductory niceties; this music plunges both violin and piano immediately into the middle of Higdon’s fiery furnace where the raw materials of texture and timbre are forged along with some notational wizardry to create a multi-layered, multi-movement work that’s a rare marvel these days: no hint of composer “see what I did” self-indulgence or impenetrable “you can’t understand this without a playbook” construct. What Higdon offers is five movements that are intriguingly varied (hard and fast, moody/contemplative, jaunty, etc.), never too long (that is, never lacking ideas or how to develop them), and always technically assured in the manner of one who intimately knows both instruments. Higdon’s use of stopped piano strings for the work’s odd-numbered movements is certainly a nice touch that, far from a mere gimmick, adds unusual colors that sometimes gives the impression of a third instrument playing.

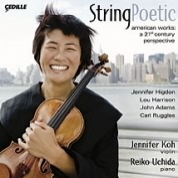

Jennifer Koh, for whom String Poetic was written, plays with such powerful, right-to-the-edge virtuosity, and the recording is so expertly engineered that you easily forget about amplifiers and speakers and just become absorbed into the violinist’s and music’s presence. And let’s not forget pianist Reiko Uchida, whose part seems every bit as formidable as Koh’s, and whose own virtuosity is just as impressive.

Of the program’s remaining works, Carl Ruggles’ Mood probably is the more mystifying and interesting (and it fits well here even though it was written 70 or more years before the disc’s other pieces!). Ruggles was a non-conformist whose brand of atonality can be alternatingly grating and sensual (in a gritty sort of way!), the strings of dissonances seeming more accidental than planned. A famous story goes that a friend arrived at Ruggles’ Vermont house for a visit, waiting outside his studio for more than 10 minutes while the composer banged relentlessly a single chord on the piano. When he finished, the guest entered and asked Ruggles why he had kept playing the same chord over and over for so long. “Because,” he replied, “I was thinking of using it in a piece and I just wanted to see if it held up.” Who knows whether that chord ever made it into a composition: Ruggles was constantly making sketches and notes, leaving his ideas unfinished and moving on to another. Mood is a transcription/reconstruction of some Ruggles sketches made by his friend John Kirkpatrick after the composer’s death, and it embodies all of the above characteristics–grating, grittily sensual, dissonant–and again, Koh and Uchida give full measure to important matters of texture and timbre, never letting up on energy or momentum for the work’s six minutes.

Lou Harrison’s Grand Duo certainly lives up to its name–for me its nearly 31 minutes is about seven or eight too many–but the two performers leave no doubt about their commitment to exploit its many facets and moods: the first-movement Prelude is a marvelous, many-colored evocation of something ancient and mysterious; the Polka is one of the wildest dances you’ll ever hear. As the notes mention, in the Stampede and Polka movements Harrison also writes “complicated octave patterns” for the piano that Uchida manages by means of a special “octave bar”. John Adams’ concluding Road Movies is a fun, lively, rolling, meandering, ostinato-laden, pulse-and-rhythm-shifting, three-movement piece, light-hearted and serious (both moods admirably captured by Koh and Uchida), and just plain irresistible for all of its 16 minutes. If you love the violin and piano and you want to come away with a happy experience (73-plus minutes) of listening to some relatively modern works, don’t miss this! Highly recommended. [5/21/2008]