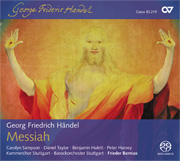

This is a very good Messiah–excellent in many respects–and it would have been among the reference versions but for a couple of issues. Thankfully the four ideally chosen soloists respect period-performance style with tasteful, durable, judiciously placed ornaments that justly enhance the expressive character of the airs and recits without (but for one notable exception) the “look at me” gestures that may work one time in a concert but don’t hold up well over repeated listening. The exception: tenor Benjamin Hulett’s silly 12-second-long (no kidding) first syllable on “Comfort…” in the fifth bar of his opening recitative. Yes, the unaccompanied measure is marked ad libitum, but really! This is an unjustifiable indulgence that distracts from the sense of the text and violates the spirit of the music. Conductor Frieder Bernius, who makes consistently intelligent, musically wise decisions throughout the rest of the performance should have squelched this unnecessary piece of theater. Okay, it’s only a few seconds out of a couple of hours’ performance, but its sheer audacity and incongruity with the rest of the reading makes it an issue.

But most Messiah aficionados will find ample cause for praise, especially in the chorus’ well-articulated phrasing and clean execution of individual lines, delivered without ever sounding precious or self-conscious. “Behold the Lamb of God” probably is the most sensitively sung, evocatively phrased, and ideally paced version on disc. Likewise, you would be hard pressed to find a more beautifully rendered “He was despised” aria than Daniel Taylor’s. This is one of Messiah’s potentially more tedious moments, but Taylor and Bernius bring it an engaging immediacy that it rarely achieves, highlighted by the impressively articulate orchestra’s gracious imitation of Taylor’s ornaments near the aria’s end.

There are many such moments in this performance, including Peter Harvey’s “The trumpet shall sound” and Hulett’s opportune explication of the air/recit sequence from “All they that see Him” to “Thou didst not leave His soul in hell”. The choruses are dynamic and exceptionally well sung–but with one major caution: if you are interested in clearly understanding the words the choir is singing, you will be disappointed because for the most part the vowels and consonants are absorbed into the overall choral texture and timbre. And this is a shame because it’s obvious that the choir knows its stuff.

Bernius is very successful with his choice of tempos–and with this virtuoso choir of 30 voices, even the very rapid “And He shall purify” and “His yoke is easy” somehow sound perfectly natural and, well, “easy” rather than forced or rushed as these choruses often do. The pace of the soprano aria “Rejoice greatly” was a bit too ambitious, however, as the otherwise fine Carolyn Sampson shudders rather than sails through the long, fast melismas. Peter Harvey is absolutely superb in his tour de force arias “Why do the nations” and “The trumpet shall sound”, and if you’re wondering, the “Halleluja” chorus is remarkably effective in Bernius’ slightly understated yet rhythmically dynamic rendition.

Happily, no big fuss is made over editions, alternate arias, performing forces, or attempting to reconstruct a particular one of Handel’s performances–although just a little information regarding performance choices would have been nice, other than, in tiny print, the notice that Ton Koopman’s “new Urtext edition” (published by Carus) was used. It turns out that this edition contains “all the surviving alternative versions of the solo movements”, allowing the director to choose whatever combination he wishes. What Bernius has done is to present the arias as we usually hear them–no surprises–which is another good decision if you wish to produce a potential reference recording of this work. Although this isn’t it, it’s definitely exceptional–and recommendable–for the reasons listed above.