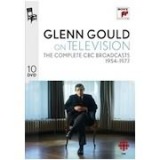

Glenn Gould fans undoubtedly will welcome the iconoclastic pianist’s complete television broadcasts for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, all remastered from the best possible sources. While much of the material previously appeared in anthologized form via Sony’s out-of-print Glenn Gould Collection released on VHS and Laserdisc, here the broadcasts are presented complete as originally aired, from small isolated flim clips to complete, full-length programs. Only one item is missing: a 40-minute interview portion from the 1970 show The Well Tempered Listener that could not be cleared for release.

While production values often appear stilted and dated by modern-day standards, Gould himself remains an utterly riveting presence. The first existing footage of Gould, a 1954 concert performance of the Beethoven First Concerto’s opening movement (replete with the pianist’s own, rather stylishly contrapuntal cadenza), reveals that all of his salient traits were in place at age 21.

Already you see Gould sitting abnormally low at the keyboard, conducting with whatever hand was unoccupied, and humming along. Yet his body language is fluid rather than contorted, and often provides an ecstatic counterpart to his uncannily precise and highly articulated finger-work, not to mention his acute sense of line no matter how complex the textures. For example, the rapid left-hand arpeggios in the first movement of Beethoven’s “Tempest” sonata display a driving urgency yet couldn’t be more clearly projected.

Five full-length shows (The Subject is Beethoven, Music in the U.S.S.R., The Anatomy of Fugue, Glenn Gould on Bach, Anthology of Variation, and Richard Strauss: A Personal View) feature Gould’s brilliantly analytical comments interspersed with performances that include works unrepresented in Gould’s studio discography, such as Webern’s Variations for Piano, Beethoven’s Op. 69 Cello Sonata (with Leonard Rose), and the first movement of Strauss’ Violin Sonata (with Oscar Shumsky).

The aforementioned Bach show from 1964 includes the nine Goldberg Variations canons in a performance that sits stylistically halfway between Gould’s brisk and brash 1955 Goldberg debut disc and his more reflective 1981 remake. A congenial 1966 collaboration between Gould and Yehudi Menuhin in Bach’s C minor sonata, Schoenberg’s Phantasy, and Beethoven’s G major sonata Op. 96 finds the violinist on excellent form–and Gould at his most provocative.

There’s also a rarely-seen film version of Gould’s radio documentary The Idea of North, where director Judith Pearlman’s spacious imagery and subtle montage effects add welcome context and dimension to the original audio-only production. Gould’s collaboration with Karel Ancerl and the Toronto Symphony in Beethoven’s “Emperor” Concerto came about when the original piano soloist Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli cancelled at the last minute and Gould stepped in to substitute.

By contrast, Gould’s final CBC television project Music In Our Time resulted from careful scripting and well-considered program building, which extended to composers Gould ordinarily shunned, such as Poulenc, Debussy, and Ravel. Indeed, Gould’s “de-orchestration” of the latter’s La Valse for piano solo reveals a sense of abandon and being on the edge that we normally do not associate with Gould’s Apollonian control.

For me, however, the high points of Gould’s CBC television legacy are the four 1966 programs entitled “Conversations with Glenn Gould”. Each focuses on a specific composer (Bach, Beethoven, Schoenberg, and Richard Strauss), with Gould illustrating at the piano and sharing stimulating, humorous insights with interviewer Humphrey Burton.

In the Mozart program, Gould demonstrates his deliberately deconstructed interpretation of the A major K. 331 sonata’s first-movement variations alongside a more conventional reading that’s perhaps more beautiful and convincing than Gould would have conceded. The Strauss program contains brilliant samples of Gould’s improvising prowess, plus an extended excerpt from Elektra. Many Gould commentators cite the latter as a “transcription”, but it’s really nothing more than Gould playing the vocal score piano reduction like a man possessed.

An enclosed booklet includes complete personnel, air dates, full production credits, and a succinct, informative essay by Tim Page. Obviously a good deal of care and intelligence went into releasing this body of work in the right way, for which scholars, collectors, piano mavens, and music lovers alike should be grateful.