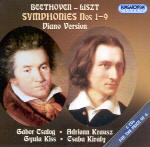

Like Harmonia Mundi’s cycle devoted to the Liszt/Beethoven Symphony transcriptions, Hungaroton splits the playing chores among different pianists. Gábor Csalog is heard in the First, Third, and Eighth Symphonies, and Adrienn Krausz takes on the Second, Fourth, and Sixth. Whereas Harmonia Mundi recorded Liszt’s two-piano arrangement of the mighty Ninth, it is the far more challenging solo version Csaba Király tackles here. The Fifth and Seventh Symphonies feature Gyula Kiss, the only one of these four pianists I’ve previously encountered either live or on disc. As it happens, Kiss’ traversals of the Fifth and Seventh comprise this cycle’s weakest components. Arguably the most difficult of these transcriptions (after the Ninth), the Seventh’s myriad challenges push Kiss’ technique and stamina to the brink. She fares no better in the Fifth’s outer movements in the way her dogged literalness erodes the music’s brio and rhythmic momentum. She commences the Scherzo at a tempo she can manage comfortably enough, but when the famous double bass passage enters in the form of piano octaves at the Trio’s outset, she slows down in order to accommodate her hands. Neither Beethoven nor Liszt asks for a tempo change, by the way.

By contrast, Csaba Király’s honest musicianship and well-schooled fingers easily command the Ninth’s dauntingly dense textural labyrinths in the opening Allegro, and weave the choir-less finale’s diverse components into a cogent whole. Compared to Cyprien Katsaris’ supplementary octaves, imitation drum whacks, and other textural modifications, Király is more faithful to what Liszt actually wrote down. But his dry, monochrome sonority and detached, matter-of-fact interpretive outlook project next to nothing of the music’s dramatic scope and architectural vision.

Solely on the basis of these recordings, Adrienn Krausz draws upon a larger arsenal of tone color and dynamics than his three colleagues do. He is most impressive in the Second Symphony, where he smoothly negotiates the first movement introduction’s transition into the Allegro proper, which he suffuses with easy propulsion. Krausz has no trouble with the Finale’s notes, but Konstantin Scherbakov’s more assured and fluid pianism boasts superior characterization and timing, here and overall. In the larger-scaled Third and Sixth, Krausz’s little hesitations and tiny pauses (to ensure greater accuracy?) not only break the composer’s line of thought, but grow increasingly wearisome as the performances progress.

On balance, Gábor Csalog’s three contributions are the strongest in the set. He brings admirable clarity and style to the First and Fourth Symphonies in a manner that may strike some listeners as a pianistic mirror to the sobriety and forthrightness of Karl Böhm’s Vienna Philharmonic Beethoven cycle. Csalog is particularly attuned to the Eighth’s rustic humor and unbuttoned spirit, and, in fact, tosses off the Finale’s tricky repeated notes more steadily and securely than the normally invincible Katsaris. The latter’s complete cycle, however, remains the reference version for those who want all the Beethoven/Liszt symphonies in one package.

For a less flamboyant point of view, Leslie Howard’s versions rank high in the scheme of his alarmingly uneven complete Liszt survey for Hyperion. And perhaps EMI will reissue Idil Biret’s 1985-86 recordings, digitally made but never released on CD. We also wonder if the formidable promise of Scherbakov’s Second and Fifth will materialize into a complete cycle for Naxos. Add to this list Earl Wild’s First and Glenn Gould’s Fifth, and you’ll no doubt infer that the Hungaroton cycle faces an uphill battle in the Beethoven/Liszt sweepstakes.