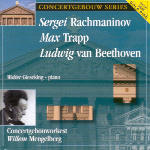

Mengelberg and the Concertgebouw may get top billing, but piano soloist Walter Gieseking chiefly commands our attention here. Keyboard mavens may be familiar with the pianist¹s 1940 broadcast performance of Rachmaninov’s C minor Concerto from earlier CD transfers. Put simply, it’s a blazing, impassioned, decisive, and utterly committed performance on all counts. Those who only know Gieseking’s patrician Debussy or bejeweled Mozart will be shocked to hear this pianist shape Rachmaninov’s arching lines with such force and freedom. He torpedoes full speed ahead into the third movement’s opening arpeggios and never lets up. Mengelberg’s firm, propulsive support plays no small part in the performance’s success; ditto for the excellent soloists within the orchestra’s ranks. There¹s little sonic difference compared with Music and Arts’ transfer, save for the latter’s slightly brighter equalization of what appears to be identical source material.

The 1931 Piano Concerto by the obscure German composer Max Trapp (1883-1971) also showcases the full dimension of Gieseking’s virtuosity in a 1935 broadcast of the work’s Dutch premiere. In fact, this is the earliest live recording extant with Mengelberg and the Concertgebouw. The first movement’s opening moments evoke Ravel’s long-lined motives in Daphnis et Chloé but quickly evolve into busy, late-romantic chromatic puffery à la Reger and Pfitzner. Imagine two Prokofiev concerto finales played simultaneously and you get a semblance of what the perpetual motion third movement sounds like. The slow movement’s uncluttered lyrical calm appeals to me more. Gieseking’s pellucid touch and rounded projection ennoble the music, as do the superb solo instrumentalists (especially the warm-toned, eloquent cellist). I haven’t heard Tahra’s transfer, which supposedly inserts a silence at the 4:07 point in the slow movement due to defective acetate. The present transfer, however, contains no noticeable gap or incision at that point, at least from what I can tell from careful listening without access to a score.

No date is given for the Beethoven Egmont Overture, but it’s actually from an April 29, 1943 concert. The sound favorably compares to Mengelberg’s 1926 and 1931 studio recordings (also with the Concertgebouw), with more presence to the timpani whacks and firmer underpinning to the bass line in the opening 3/2 section. That said, I prefer the higher degree of orchestral discipline in Mengelberg’s 1930 New York Philharmonic Egmont, despite its dry, compressed sonics. If you fancy historic piano recordings, you should have the Gieseking Rach Two in your collection.