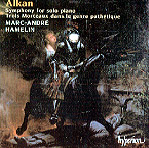

Marc-André Hamelin’s freakish proficiency at the piano both suits and serves Alkan’s music to extraordinary ends. He accomplishes technical miracles in the Symphony for Solo Piano (Nos. 4-7 of the composer’s magnum opus, the 12 Études dans tous les tons mineurs Op. 39) that other pianists would sell their souls to achieve, whether they admit it or not. Take, for instance, the Scherzo movement’s ricochet jumps from octaves to chords and back. Hamelin brings these off with the utmost in unfudged, decisive precision while still micromanaging the dynamics, the balances within each chord, and spacing of each note. Listen to the cyclonic passagework in the outer movements. Hamelin’s fingers make every bloody quaver (be it hemi, demi, or semi) sound without losing the music’s paragraphic grip or sacrificing tonal control for one nanosecond.

In the Marche funèbre, Hamelin’s staccato chords cut with the quickness of a state-of-the-art guillotine yet never sound percussive–you can ascertain each pitch. There are, of course, other ways to play this music. Raymond Lewenthal’s diabolic joy-ride through the Presto racks up a higher goosebump count by journey’s end; and Jack Gibbons’ spontaneous combustion pianism takes an equally convincing “devil-may-care” attitude toward this composer’s stupefying demands. You might say that Gibbons plays the loose-cannon Daffy Duck to Hamelin’s cool yet devastatingly effective Bugs Bunny.

No pronoun trouble, wrong turns at Albequrque, or any other slips divert from the perfect diction and inhuman evenness of Hamelin’s trills and chromatic runs throughout the three rarely-heard Morceau dans le genre pathétique. True, even Hamelin’s genius can’t fashion a silk purse from the tawdry poundings of the mercifully short Alleluia Op. 25. But that’s only one piece; the rest of the music will fascinate listeners interested in Romantic piano music’s less traveled mazes. One day Hamelin’s growing Alkan legacy will be spoken of in the same breath as Schnabel’s Beethoven, Gould’s Bach, Katchen’s Brahms, Horowitz’s Scriabin, Gieseking’s Debussy, Michelangeli’s Ravel, and Larrocha’s Albéniz. Remember where you first saw that, folks! Read the thoughtful annotations, revel in Hyperion’s usual sonic splendor, and above all get to know the strange, unique sound world of Charles-Valentin Alkan through his unrivaled interpreter. [9/18/2001]