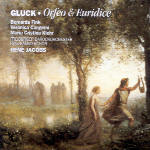

Would it be too bold to say that this version of Orfeo & Euridice is the most moving, beautiful, and simply right in a very crowded (and worthy) market? Listen and believe: Neither stinting on overt theatrics nor pathos, René Jacobs has managed to remove Orfeo from its exquisite shelf, normally labeled “reform opera”, and present it as a drama never previously heard or discussed, and therefore without its baggage. He and his sublime players lunge into the overture at great speed and with tremendous energy and thrust, percussion thwapping, truly preparing the audience for an “event”. The sad opening chorus, with Orfeo’s sadder interpolations of Euridice’s name, therefore affects us even more–the contrast is palpable–and the entire opening scene, lament after lament, is heartbreaking. Orfeo begins to rail against the gods and his sorrow turns to rage. At every turn, mezzo Bernarda Fink finds the right tone for the hero; her use of shading and dynamics is masterly. Amore, in the person of Maria Cristina Kiehr, is innocent and white-voiced (if also tempting) and gives Orfeo hope; his confusion grows as he accepts the challenge. The infernal start of the second act is ice-cold rather than boiling hot, with Gluck’s dissonances underlined with trepidation as the chorus warns Orfeo. Their dialogue is a true dialogue; Orfeo is steadfast, and the chorus retreats, pianissimo, to the distant sound of thunder as Orfeo enters Hell.

I won’t take the rest of the opera step-by-step, but suffice it to say that the Elysian Fields music never has sounded so lovely or so serene, and Orfeo’s reaction to its serenity never has seemed so honest and relieved. And so it goes–each scene comes vividly to life, each situation rings true. The playing of the woodwinds is ethereal, almost unreal, as calming as the monsters’ music was disturbing. The couple is reunited. For once the exchange between them at the start of Act 4 seems like a genuine predicament (Euridice nags almost as much as Desdemona) and it’s easy to see why this Orfeo can’t resist his Euridice, so vivid is Veronica Cangemi’s way with the text, so sweet and convincing her pleading. And Jacobs’ rhythmic forward propulsion in their duet adds urgency. When Orfeo does look back and Euridice disappears, our hero is beside himself, leaning more on chest voice than ever before in the performance. “Che faro…” is breathtaking in its simple sadness. Throughout, startlingly, Jacobs allows his singers to embellish the vocal line somewhat (horror of horrors, true Gluckians may feel), and in the lament the generous use of appoggiaturas underscores the character’s grief. What more can I say? This is a divine performance, on a par with Jacobs’ ground-breaking, fascinating Cosi fan tutte of a couple of years back. If you own only one recording of this opera, this should be it. And if you have a favorite, I bet this one will either replace it or tie it for first. [12/27/2001]