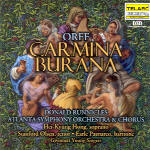

This lively, lusty, stunningly recorded new Carmina Burana goes right to the top of the heap, sharing pride of place with the celebrated performances of Jochum (DG), Kegel (Berlin Classics), Blomstedt (Decca), and Ozawa (RCA). Everything goes right, and virtually every single piece has something distinctive about it. The two opening numbers of Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi explode swiftly out of the starting gate, setting the stage for excitement that never lets up. Even the segues from one song to the next have been perfectly timed–most impressively in the third part (Cour d’amours), which builds to a huge climax marking the return of O Fortuna.

As with all great performances of Carmina, the conductor–in this case Donald Runnicles–extracts wonderful dabs of color from Orff’s neo-primitive accompaniments. Three examples (of many) stand out: the tubular bell strokes that mark the ends of stanzas in Ecce gratum; the sweetly dissonant oboe counterpoint (specifically marked “espressivo” in the score) to the flutes in Amor volat undique’s ritornello; and the forward massed woodwinds in Blanziflor et Helena. It goes without saying that the Robert Shaw-trained Atlanta Symphony Chorus sings with amazing precision and ideal blend, but whereas Shaw’s previous recording for Telarc was blandly correct, Runnicles has his singers and players fully involved in realizing the meaning of these colorful texts. Some sections simply have never been done better: specifically, from Part I’s deliciously hesitant Round Dance (Reie) to the brilliant brass playing of its last number (Were diu werlt alle min), Part II’s Ego sum abbas, and in Part III, a really angry Circa mea pectora followed by the amazingly virtuosic Si puer cum puellula.

Matching the excellence of chorus and orchestra are three terrific singers. Stanford Olsen’s roasting swan aptly sounds simultaneously comical and terrified, and he’s not afraid to make an ugly noise where his solo requires it. Hei-Kyung Hong sings her two long solos (Amor volat undique and In trutina) exquisitely and affectingly, and Runnicles chooses flowing tempos that allow her to really phrase the melodies and take those very long notes at the ends of both numbers in a single breath. Her stratospheric Dulcissime has just the right sense of abandon, and fantastic diction to boot. Earle Patriarco’s light baritone makes him sound almost like a tenor, and his tight vibrato might not be to everyone’s taste. It’s a curious vocal timbre, all top and bottom. But my, how he lives the words! Omnia sol temperat is an ecstatic reverie; in Ego sum abbas he’s obviously plastered; and Dies nox et omnia positively exudes gentle longing–a remarkable performance.

Telarc’s recording sets a new standard for this work. Every word of the text comes across clearly but never at the expense of the orchestra. O fortuna features a bass drum that sounds as if the hammer blows from Mahler’s Sixth wandered in to help out, and the great crashes on the tam-tam that so many performances shamefully bury in a muddy welter of sound cut right through. Certainly it’s an “audiophile” production, but the sonic splendor serves the music at every point, and in so doing sets the seal on a truly splendid achievement. I’m not trading in the Carminas listed above, but I suspect that when I want to hear this work anew, and especially if I want to turn someone else on to it, this will be the version of choice. I wouldn’t be surprised if a single listen makes it yours too. [4/7/2002]