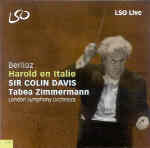

If all of the Colin Davis/LSO Live productions were this good you would think this partnership the finest in the world. Whatever the pluses and minuses of his remakes of Dvorák and Holst, and his variable forays into Bruckner and Elgar, when it comes to Berlioz Davis still delivers the goods as do few others. This is a scorcher of a Harold in Italy, swifter and even more rhythmically emphatic than his previous Philips recording, and in Tabea Zimmermann it has a viola soloist as characterful as Davis’ conducting and the LSO’s playing. The flowing opening sets the stage for a positively luscious presentation of Harold’s themes, Zimmerman’s dusky tone seeming to drink in the timbres of the accompanying winds and harp. But once the first movement gets going, watch out! The music flies along as if self-propelled.

The Pilgrims’ March also wastes no time getting started (these are certainly happy pilgrims); but then Davis and Zimmerman create a marvelously atmospheric moment when the chorale theme (Berlioz’s “Canto religioso”) appears at the softest possible dynamic in winds and strings accompanied by sul ponticello arpeggios in the viola–a magical passage. The winds of the LSO make a particularly distinguished showing in the Sérénade, with oboe and English horn turning in an amazingly pure unison in the slower central episode while the rustic piping of the outer sections is perfectly caught. The final Orgy of Brigands really is “frenetico”–and then some. Davis whips the orchestra up to a fine frenzy, but never for a moment does he sacrifice rhythmic accuracy or permit a jot of loose ensemble. It’s an impressive demonstration of collective virtuosity, and just what the composer ordered. The Ballet music from Les Troyens makes an apt encore to a truly great performance of this perennially fresh score.

Happily, the LSO engineers have managed sonics from the notoriously difficult Barbican that rise to the occasion. The venue’s natural dryness serves only to enhance the music’s rhythmic point and never turns boxy or desiccated. Balances between soloist and orchestra sound natural without excessive spotlighting (Zimmerman’s big, round tone renders such tactics largely unnecessary), while the ensemble has a coherence and sectional integrity often lacking in these productions. Timpani aren’t excessively prominent, the brass section makes its points and adds weight without blasting (note the impressive but not overbearing “lourdement” sections in the finale), and the piccolo whistles brightly but not painfully on top of it all. This is the sort of achievement we expect to hear from these forces; let it be the standard by which future projects are measured and evaluated for release. [7/5/2003]