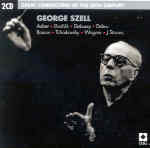

George Szell certainly merits inclusion in a series devoted to the last century’s great conductors, but this collection tells us little we didn’t already know about this well-documented maestro. One thing it does demonstrate is that Szell could get admirable results even when he was a podium visitor away from the Cleveland Orchestra he molded into one of the world’s greatest. Another is that, unlike so many of his peers, he could duplicate the experience of a live concert in his studio recordings, so the included “live” recordings of works he recorded in the studio don’t differ much in mood or detail. Finally, the widespread belief that Szell was a tight-lipped, unsmiling conductor is proved false since the Rossini overture here is done with a smile. The shorter pieces are fillers, preludes and postludes to the main events.

While even Szell couldn’t make the Delius interesting, the razor-sharp Rossini, vibrant Auber, live Wagner, and the danceable Strauss waltz that he makes sound like Cleveland-on-the-Danube, are welcome. His Dvorák Eighth is a reissue of the 1970 EMI recording, not the better-known, preferred earlier Cleveland one available on Sony. This one demonstrates no falling-off in the quality of playing, is only slightly different in detail, and is as idiomatic and enjoyable (with a lovely Allegretto and greater flexibility than Szell’s critics ever gave him credit for). But the passage of time has not led to any forward leap in sonics, as EMI’s slightly opaque sound indicates its engineers hadn’t solved the problems of recording in Severance Hall.

Szell also recorded the Tchaikovsky and Debussy works with the Cleveland Orchestra for Sony, and EMI here includes them in live broadcast recordings with the Southwest German Radio Symphony of Cologne. Again, differences are minimal. The dry-eyed Tchaikovsky Fifth is exciting but scrubbed squeaky-clean of the heart-on-sleeve angst most of us want (even if we deplore emotional excess). The Debussy is brilliant and full of flashing colors. There’s no Beethoven, Mozart, or Haydn, and none of the moderns Szell played so well, such as Walton or Dutilleux. And the Wagner item serves as a reminder that EMI should have devoted more space to Szell’s neglected association with the New York Philharmonic.