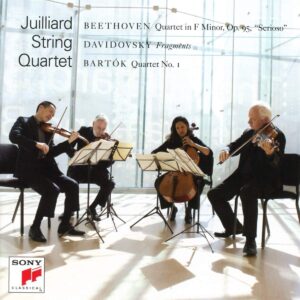

Recorded in 2017 to mark its 70th anniversary year, the Juilliard Quartet’s most recent release reflects the ensemble’s decades-long mandate to champion new works, and also revisits two Juilliard repertoire staples. Mario Davidovsky’s Fragments (String Quartet No. 6) typifies this composer’s propensity for jagged dissonant phrases that morph into long sustained tones, soft clouds of high-register chords, petulant ponticello effects, and murmuring trills that provide a backdrop for bold melodic gestures. It’s the kind of music that’s long been associated with the Juilliard Quartet, and the current lineup delivers the goods, fusing rhythmic rigor and coloristic fantasy to convincing effect.

It’s interesting how the astringent sonorities and motoric drive the players bring to Beethoven’s “Serioso” quartet are conceptually similar to the Juilliard’s earlier stereo RCA Victor and 1981 CBS Masterworks recordings. The main difference is that the first violinist in the 2017 recording, Joseph Lin, is not averse to employing a wide range of vibrato and discreet portamentos, in contrast to the late founding first violinist Robert Mann’s leaner, tauter style. The Allegretto movement in particular features a wide array of personal nuance and inflection, yet never at the expense of ensemble congruity. Much as I appreciate the group’s thrusting dotted rhythms in the Allegro assai Vivace movement, they arguably push too hard to make their point. In this respect I prefer the equally exciting yet lither, cleaner Quartetto Italiano interpretation.

Before hearing the Juilliard’s newest Bartók First quartet, I listened again to the 1950, 1963, and 1981 Robert Mann-led recordings. In essence, the execution grows increasingly effortless and the response to the composer’s expressive directives becomes more simplified and refined over time. The present recording, however, brilliantly restores the music’s fervent intensity and youthful ambition. In the first movement, for example, you’ll note violist Roger Tapping virtually foaming at the mouth in the molto appassionato passage (four measures after rehearsal number 6 in the Boosey & Hawkes score), making the most out of the rapid diminuendos. The Allegretto’s opening duets (viola and cello together, followed by the violins) gain character and point by virtue of the 2017 incarnation’s meticulous attention to issues of articulation; you really hear distinctions between slurs, slurred staccatos, underlined notes, accented notes, and so forth. And listen to cellist Astrid Schween’s explosive, full-bodied solo in the transitional introduction to the finale; she plays as if her life depended on it, in contrast to 1963’s cooler-headed Claus Adam.

In sum, the Juilliard String Quartet remains an American institution characterized by stability, integrity, and the capacity to honor tradition and embrace change at the same time.