[A re-post from our archives in memory of conductor Andrew Davis, February 2, 1944-April 20, 2024.] Neither an opera nor an oratorio, this unique work–certainly unique to Berlioz, but also to the canon of “dramatic” choral music–is, to coin a phrase that defines little, placidly holy. If your familiarity with and passion for Berlioz stems from his Requiem, Te Deum, and La Damnation de Faust, you will be disappointed. An open mind will leave you stunned by L’Enfance du Christ’s pastoral beauty, its intimacy, and an aura that borders on the innocent.

High drama radiates through the first of its three parts, with Herod at its center: he narrates a dream, he ruminates, he expresses terror, and then he demands that newborns be slaughtered to make certain that the prophesied Christ never gets to be the threat Herod fears. From there we follow the Holy Family, having been forewarned by angels, on their voyage to Egypt to avoid the murder, and eventually to their arrival in Egypt where they are offered sanctuary. After they are safely sheltered, Berlioz pulls out a trump card in the form of a trio for two flutes and harp of such unique sonority and gentleness that, once heard, cannot be forgotten. Throughout, Berlioz uses mostly a slimmed down string section with winds, often in solo parts.

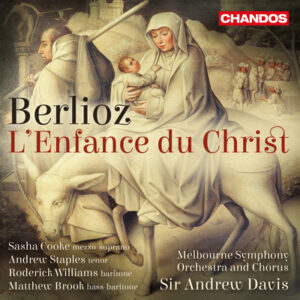

The marvelous solo singers are utterly convincing, from Andrew Staples’ mellow tenor as the Narrator and Matthew Brook’s complex Herod, to the love of Joseph and Mary (Roderick Williams and Sasha Cooke) for their baby and their rush to escape. The chorus of the Melbourne Symphony as shepherds and angels is dreamily lovely. There are several fine performances of this work on CD, and this one ranks among the best. Andrew Davis and the Melbourne Symphony seem to revel in the refined, translucent scoring, and when all is said and done this performance leaves you with a sense of sweet mystery that is as powerful as bombast and breast beating.