Reviewing performances—live or recorded—by mezzo Joyce DiDonato is becoming repetitive. You wait for a flaw—an aspirated run, a note out of tune, a rote performance, a dropped note among cascades of 16th notes, a trill that does not catch perfectly, a lack of involvement or shallow characterization, a line lacking in legato or smooth emission, a strained high note, a shortness of breath, a da capo embellishment out of sync with the era or composer, a misuse or overuse of chest voice—but to no avail.

And she does not show off for its own sake. In this set of 13 arias DiDonato presents us with queens, princesses, sorceresses, empresses; some we’ve heard of (Handel’s Cleopatra and Alcina, Monteverdi’s Octavia, Haydn’s Armida), many we have not (Keiser’s Octavia and Galsuinde, Giacomelli’s Irene); and all are in one or another sort of distress. Galsuinde, the heroine of Keiser’s Fredegunda (I’m not making this up), sings “Let me weep/Then let me die; My dearest, grant me the bitter consolation in my suffering.” This gorgeous da capo aria is so beautiful that it’s heart-stopping, and DiDonato sings it with such resignation and pathos—no fancy roulades, no multi-octave leaps, just a long, beautiful melody and stupendous use of portamento for added sadness and warmth—that the five minutes it takes to do so just stand still. The da capo section is, of course, decorated, but with some darker tones.

Alcina’s “Ma quando tornerai”, a rage aria, is here taken faster than anyone might have guessed possible, with each word, each surge of notes spat out with venom: DiDonato leans on her voice as if each note counted. And the pleading B section is just that—a true yearning for her love with the full knowledge that he will not capitulate, leading to even more anger. This is not singing by the numbers.

And if you haven’t heard of Irene, Princess of Trebisond, from Giacomelli’s Merope (shame on you!), you’ll wish you knew the entire opera after hearing the unbearably tragic “Sposa, son disprezzata”, the lament of a despised wife with an unfaithful husband. By contrast, Berenice (from Orlandini’s opera of the same name) is clearly in a suicidal rage—what else would drive her to such maddening melismas? And with the orchestra’s strings slashing away under her melody? Shocking! In a long recitative-arioso Monteverdi’s Octavia sings of the plight of women in a male-dominated society with almost stupendous bitterness.

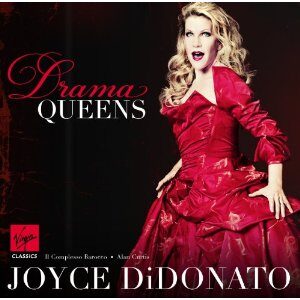

Why continue describing what goes on here? Alan Curtis has found a “drama queen” (in the best sense) so stupendous that he and his Complesso Barocco seem to be following her every mood with sharp attacks, rapid-fire playing and, when called for, tender, sensitive longing. Sonics are ideal—spotless and natural. This is simply glorious.