There is a handful of frequently recorded operas, all considered “challenging works”, that have never had a bad recording. One can come across, without searching too hard, a mediocre Bohème, an undercast Butterfly, a lackluster Cosi fan tutte, and an Aida or Don Carlo or Puritani featuring a soprano or tenor or bass not up to their tasks under a conductor who lacks sensitivity, or shows a lack of sympathy for or understanding of a singer or character. Any of these can sink the whole recording. But Falstaff, Pelléas et Mélisande, Parsifal, and Elektra, to name four, have never suffered such a sinking. Each has numerous recordings, all of which will offer great enjoyment, new understanding, and a stunning operatic achievement.

To this quartet (and I’m certain there are others) I add Benjamin Britten’s Peter Grimes. Note that David Vernier, on this website, reviewing the Britten-led, Decca recording of the opera, wrote that “Peter Grimes arguably is the most profoundly original and dramatically groundbreaking opera of the 20th century, and possibly the most significant English dramatic musical work ever written.” Not only do I second that, but just to close the argument I opened, who would dare treat such a work with other than the utmost respect? And indeed, not one of the ten available (a couple on video) is less than a wonderful listening experience, a revelation of sorts, and deeply satisfying.

The fascination with the eponymous character–hero, in this case, is a loaded term–is central. Multi-hued, no Don Carlo, no Musetta, no Ernani, no Tristan is he: Is Grimes a victim or a victimizer? “The more vicious the society, the more vicious the individual,” Britten wrote. Is he a suppressed–or not-so-suppressed–pederast? It’s a difficult subject to avoid, and the knowledge that tenor Peter Pears, Britten’s muse and the title-role’s creator, convinced the librettist to eliminate some of the problematic lines that pointed too specifically in that direction shines light on it. We know that Britten and Pears, a life-long homosexual couple, felt the cruelty of society, and to be sure, in the opera Grimes is a victim of the scapegoating, suspicious locals, whose nastiness he fuels with his anti-social behavior.

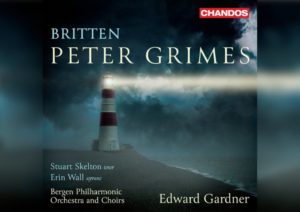

On this spotless Chandos recording, the clarity of the conducting by Edward Gardner and the work of the Bergen Philharmonic (and attendant choruses) go hand in hand to make this the most transparent recording of even the most massive moments in the score. Deceptively clear in the first scene, both orchestrally and chorally, as the opera continues the textures can become muddy. How often I’ve wished the strands of “Old Joe has gone fishing” and the first scene of Act 3 leading up to and including Mrs. Sedley’s “Murder most foul it is” were easier to follow! And here they are.

Of course the writing never allows every word to be understood (and the Bergen choruses’ diction is as good as any British company’s), but this recording allows us to hear more of the interwoven threads, orchestral and choral, than ever before. The buildup of “Old Joe…” is terrifying here; every drunken voice is heard. Similarly Mrs. Sedley’s snake-like vocal line stands out among the other nastiness. The yowling and yelling are terrifying. Use of the stereophonic stage is brilliant and vivid. And needless to say, the Four Interludes are vibrant, waves slashing, sunlight glinting. The slowly built Passacaglia is heart-stopping. Gardner knows that when Grimes is seen striking Ellen, the Borough’s suspicion turns to hatred and cruelty. It is the plot’s turning point, and we can hear the change.

As mentioned above, the interpretation of Grimes himself is central. Britten hated Jon Vickers’ approach: too angry and bullying; crazy/sentimental, not sweet/sentimental. Most of the others on disc are also of the Peter Pears/British/somewhat white-voiced variety–voice with focus and an edge that can bite. Here, Stuart Skelton is unique: his repertoire mimics Vickers’–Florestan, the Wagner roles, Canio–but his singing could not be more different.

From the opening notes the British tenors tend to sound weirdly detached and spooked; Vickers was aggressive and angry. Skelton sounds firm but sad, as if he’s involved in a lost cause. He knows he is the victim the people are looking for and he sounds as if he’s trapped; it angers him but he tries to hide it. He is sensitive but severely damaged, neither inherently violent nor dreamy, like Pears. He encompasses both–it’s a big, Wagnerian sound, but it’s not bottom-heavy. One can actually believe that he loves Ellen and thinks their relationship could work; Vickers knows he’s too mad, Pears knows he is incapable, for whatever reason. Skelton’s final scene is shattering in its tragic inevitability.

Compassion and goodness shine in Erin Wall’s reading of Ellen Orford. She probably has the loveliest and least matronly voice of any Ellens on disc, and that helps. (She died in October, 2020 at 44 years of age.) When she notices the tear in the boy’s coat, her voice takes on a quiver of terror; her positivity is being severely challenged. She goes from protective and hopeful to realistically trying to reason with Grimes, to absolutely shattered when Peter re-appears in Act 3. A mighty portrayal.

One might say the same thing about Roderick Williams’ Balstrode: what a fine character he is! Understanding, hopeful, defending until he no longer can avoid the truth. He sings with as much sturdiness as the man’s character and will–another stunning representation. Catherine Wyn-Rogers gives us an irascible, dark, desperate Mrs. Sedley, her addiction to laudanum just one of her horrid problems.

The smaller roles are all well characterized: Auntie is extra sure of her odd position in town as Susan Bickley interprets her, and her “nieces” sing handsomely as well. Marcus Farnsworth’s Ned Keene is properly slimy; Robert Murray’s vaguely fanatical and drunk Bob Boles stands out; Barnaby Rea’s Hobson sounds properly weary.

Again, bravo to orchestra and chorus–could the chill northern winds and relentless sea in their bones have helped to understand Britten’s setting? The dark instruments snarl and underpin the tragedy throughout; the violins glint as sunlight or slash viciously. Even if this becomes your third recording of Grimes, it’s a necessity.