Otto Klemperer’s recording of the Magic Flute has long been considered the recording. When it came out, in 1965, it impressed itself on so many listeners as the standard Zauberflöte–an indelible emotional footprint that still informs our hearing. It seems only right that Warner has given the most fulsome treatment for this latest luxurious re-issue.

From the start, however, this version may or may not be limited by its total exclusion of spoken text. As Shakespeare might have put it: “Text, or no text, that is the question: Whether it is more pleasant to the ear to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous librettos, or to take the scissors to a sea of words and by opposing cut them.” This question of text-or-no text especially looms with a recording of a spoken-text-heavy opera or Singspiel like The Magic Flute, and more than anything else, it’s a matter of target audience.

Non-German speakers, except the very most diligent who really follow the libretto closely even for spoken text, won’t benefit from its inclusion. Nor will those who listen to this (or any other) opera mostly for the music. True, the inclusion of the spoken text does alter the opera and makes especially Pamina look better and a lot less whiny, but for anyone wanting to explore that, the answer is, in any case, René Jacobs’ superb recording (Harmonia Mundi). At the time, producer Walter Legge and EMI’s German division both favored inclusion of text (it very likely would have been an abridged version) but Klemperer refused. Legge dryly commented: “There’s no fool like an old fool”… but the efficiency of a just-the-music recording has merits of its own. With everything absolutely performed attacca there may not be room to catch a breath, but there’s something exhilarating about the pace.

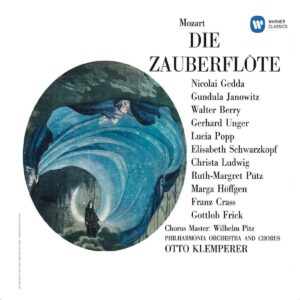

What makes it great? The casting, if we’re honest. When Legge–who assembled the cast even if he would go on to quit what was supposed to be his last production for EMI over his tussles with Klemperer–said that it was “as perfect as the world’s resource could yield”, he wasn’t even bragging. “Star-studded” rarely is as apt a description as here, when the three ladies (!) are cast with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Christa Ludwig, and Marga Höffgen. Nicolai Gedda and marvelous Gundula Janowitz as the princely couple, Walter Berry and Ruth-Margret Pütz as the feathered couple, Gottlob Frick and Lucia Popp as the (quasi-)parental units, Franz Crass as the speaker, and a slew of other veterans for even the smallest roles: Really, that’s just boasting! The resultant reviews were, as might be expected, jubilant. Many recordings have since been made, several were made before–but none has ever attained the status of this. The liner notes even attribute a (completely spurious) quote to Alex Ross saying that “there is basically no other recording”.

In truth, the Magic Flute needs heart and spirit, not an all-star cast. You want a great, agile Queen of the Night, no wobbles in Sarastro, and a fresh, preferably manly Tamino; but the rest floats or sinks with the presence (or lack) of a true ensemble, joyousness, and of course musicality. Klemperer’s recording has most of that and no weaknesses or awkward spots (i.e. Fischer-Dieskau as Papageno in imaginary Lederhosen). The sound was always good and is bettered in this remastered version–the first stereo Magic Flute in EMI’s catalog. That alone makes it one of the go-to recordings; a safe, fine choice. That said, there is no way that such a highly regarded recording isn’t also overrated.

Karl Böhm’s recording from 1955, on Decca, in still great-sounding early stereo, provides much stronger competition than contemporary reviews would have made you believe. With Walter Berry and Christa Ludwig in the same roles, but nine years younger, Wilma Lipp’s absolutely standard-setting Queen of the Night (light on the vibrato, arguably not bettered until Diana Damrau took to the part), and the lyrically-ideal Tamino of Leopold Simoneau, it’s got sublimity on its side, just the same. Klemperer and Böhm take almost exactly the same time (138 minutes) for the same amount of music. Klemperer’s tempos are more flexible–notably crisp here, regal and broad there (to use nice adjectives)–whereas Böhm’s is a continuous flow with a fine, arguably homogenizing but decidedly sanguineous pulse.

Anyone who can or wants to forgo the text–the nobly-chauvinistic, patronizing libretto, as is, would cause any number of trigger warnings if this opera were to be recklessly played to today’s crop of university students–will find Klemperer (or Böhm) still to be a rosy-cheeked standard. Warner’s presentation of this latest of umpteenth re-issues rivals the attention that was lavished on LP sets at the height of their day: Texts, photos, libretto, and quality materials make it a joy just to handle.