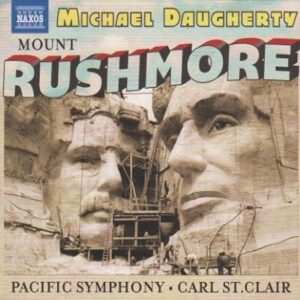

Michael Daugherty continues his musical exploration of iconic bits of Americana on this highly entertaining disc containing premiere recordings of three major works. Mount Rushmore is a cantata for chorus and orchestra in (aptly enough) four movements, each of which sets a text mostly by the president depicted in each of the mountainside’s four massive busts. Happily Daugherty creates variety by choosing a wide range reference. Thomas Jefferson, for example, contributes an Italian love song, while Lincoln is represented by the Gettysburg Address. The text setting is largely syllabic, and it would be idle to pretend that Daugherty shows much imagination in his handling of the vocal parts, but the scoring is brilliant and the work is much more than mere patriotic puffery (as the introspective ending shows).

Radio City, a three-movement “Symphonic Fantasy on Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony”, isn’t the first musical portrait of the great Italian maestro. That honor probably belongs to Don Gillis’ eponymous tone poem, which has yet to be recorded. Indeed, Gillis is the composer who Daugherty most often resembles in his “pop meets classical” aesthetic, although Gillis wins out in terms of sheer humor. Still, Radio City is a bravura vehicle for the orchestra. The opening movement casts a glance at Vivaldi and Verdi without ever descending into cheap pastiche, and it’s a tribute to Daugherty’s strength of personality that he always sounds more like himself than anyone else.

The Gospel According to Sister Aimee is another triptych, this time paying tribute to early-20th-century evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson. A controversial figure, McPherson amassed a huge following while arousing widespread suspicion for supposedly staging her own disappearance so as to run off with one of her alleged lovers, before dying some years later from an accidental overdose of sleeping pills. Brilliantly scored for organ, brass, and percussion, with the organ part vividly played by Paul Jacobs, the piece obviously comes from the same pen as the other works on the program. However, by the time I got to this last work I couldn’t help but notice one of the shortcomings of Daugherty’s language: the near total absence of counterpoint.

Tovey famously remarked of Berlioz that he “achieved everything that was possible for a composer who hated counterpoint,” and enjoyable as this music certainly is, you may well come to feel similarly about Daugherty. Certainly in a work featuring the chorus, or the organ, or both, there’s a great opportunity to indulge in some extended polyphony, even if it isn’t strict (as in a formal fugue). However exciting the performances are, and there’s no question that Carl St. Clair and the Pacific Symphony and Chorale do a splendid job, the music would benefit from a touch more textural variety to lend substance to its tuneful, splashy timbral surface. Of course this is a purely personal opinion, one that should not detract from the appeal of this otherwise beautifully engineered release.