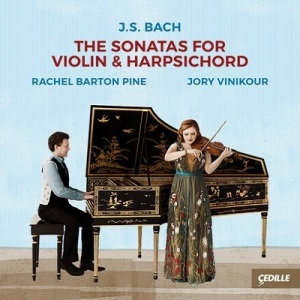

You don’t have to look very far (check out the Classicstoday.com reviews archives) to find at least a half dozen first rate recordings of these sonatas. But this is Rachel Barton Pine and, here making his Cedille debut, her keyboard partner Jory Vinikour, both of whom have long-established credentials as baroque–and Bach–interpreters. So when they “speak” it’s worth a listen. Pine plays a Nicola Gagliano violin from 1770, in its “original, unaltered condition”; Vinikour’s harpsichord is modeled after an instrument by Pascal Taskin from 1769.

I can hear some of my esteemed colleagues remarking with some measured disfavor about Pine’s “austere” tone, with its minimal use of vibrato, but what she gives us is the true, unadorned voice of this very special instrument, expressing itself in a wide range of color and articulation, refraining from a romanticized treatment of the violin lines while never retreating from the more obvious expressive character of melodies and phrasing.

This approach makes perfect sense, as these works are meant not as solo vehicles for violin, but as an equal partnership between keyboard and violin–in fact, three-part pieces, shared among the “three hands” of harpsichordist and violinist. If a true balance is to be obtained, the violin voice should not come off as the “star”, and therefore should blend as much as possible with the voice(s) of the harpsichord, which of course has no vibrato, no volume control, no way of enhancing its expressive power. So, while at first Pine’s tone may seem sparse and straight, on further listening you realize that something much more subtle is happening: she is masterfully manipulating timbre and expressive effects according to register and key and the nature of the harpsichord part.

For instance, Pine draws a remarkably rich, sweet, darker tone for the F minor sonata’s extended opening Largo. And–for my favorite of all the sonatas–she delivers a more robust, uplifting sound for the opening Largo of the C minor sonata (BWV 1017), a lovely tune reminiscent of the famous aria Erbarme dich from the St. Matthew Passion. Another gorgeous slow-movement melody–among Bach’s most beguiling–follows later, before a lively, concluding Allegro.

Pine and Vinikour give us no more and no less than what Bach’s scores dictate, and so perhaps these works are less flashy than the concertos, less intimate and virtuosic than the solo sonatas and partitas–but in these works we encounter some of Bach’s most technically intricate and fascinating creations, and these interpretations, performed with such clarity and care–in true partnership–make a good case for hearing them more prominently and more often.